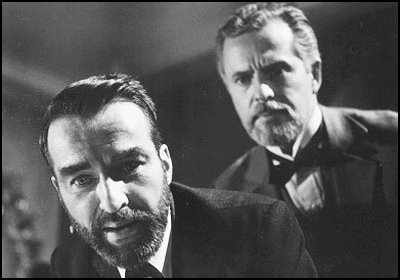

of a patient's trauma in John Huston's FREUD.

A couple of days ago, Donna and I commemorated John Huston's 100th birthday with a day's end screening of FREUD (1962), one of his more difficult films to see. This Universal release has never been available on video and, to the best of my knowledge, it's never appeared on any of the premium cable networks -- but, thanks to a friend with access to hidden reserves, I was able to see it for the first time in many years... for so long, in fact, that seeing it again was, appropriately, like exhuming a buried memory from childhood.

FREUD isn't widely regarded as one of Huston's better films; it didn't last in theaters for very long, and it made few critics' Ten Best lists in 1962. But as its proto-Star Child ending faded to black, I couldn't help but exclaim aloud, "What an astounding movie!" Rather like an Eric Rohmer film, it consists of one conversation after another, occasionally interrupted by an academic lecture, which is probably why it disenchanted mainstream audiences and critics; nevertheless, it had me by the throat from beginning to end, deriving suspense and excitement from its articulation of ideas and tentative probings of inner space. As the film ended, I felt the same elation I feel after seeing a thriller by Clouzot or Hitchcock, something that has put me through the ringer -- and then realized, with amusement, that what I'd seen was something like 140 minutes of talk. Huston himself called FREUD "an intellectual thriller."

I may be missing some other examples, but I believe there were only two major films about psychoanalysis prior to FREUD: Hitchcock's SPELLBOUND (1945) and Nunnally Johnson's THE THREE FACES OF EVE (1957); earlier movies like SHOCK CORRIDOR, THE SNAKE PIT and even THE CABINET OF DR. CALIGARI, which are set in asylums without seriously broaching the subject of psychoanalysis, should be removed from consideration, as should later but still progressive films like DAVID AND LISA and LILITH. FREUD stands apart from all these films because it is about the excitement of discovery, and the singularly great discovery of unexplored wings of the human mind -- places "as black as Hell itself." Because it is the story of the first steps taken toward psychoanalysis, and because its protagonists are academics, it also offers us the rare opportunity to see people conversing on higher and deeper levels of awareness, and dawning awareness, than other films almost never aspire to attain.

I'm familiar with Huston's reputation as a big-time drinker, but I don't know how much experience he had, if any, with psychedelics. He made this film at a time when LSD therapy was legal and quite au courant, and the high-contrast scenes visualizing Freud's attempts to dredge information up from the subconscious and unconscious of his patients have as potent a lysergic edge as anything I've seen this side of ALTERED STATES. The movie encourages the viewer to look below the surface of everything and everyone involved, and manages to reveal a surprising amount of information without ever expressing it on the surface, or "consciously." For example, one senses that the misplaced love felt by the patient Cecily (Susannah York) for Dr. Breuer (Larry Parks) was in fact reciprocated, though this is never admitted, and that this was the true reason why he places Freud in charge of her care. Likewise, it is left to the viewer to recognize the actress playing Freud's wife Martha (Susan Kohner, the daughter of Lupita Tovar and Paul Kohner) as a "reflection" of the actress playing his mother (THE HAUNTING's Rosalie Krutchley), and to leap to the discovery of the "Freudian slip" before Freud himself. Also worthy of mention are an outstanding, disturbing scene showcasing the talents of a young David McCallum and, to move from the sublime to the ridiculous, a single line by one actor that is somewhat glaringly looped by Paul Frees.

FREUD, like SPELLBOUND before it (and Corman's PIT AND THE PENDULUM, come to think of it), helps to establish a narrative of process and revelation that points the way to a specific kind of Italian gialli -- the kind that build toward a cathartic understanding of the killer's moment of trauma. Mario Bava, I think, was the first to import this into the gialli with HATCHET FOR THE HONEYMOON, and it resonates throughout much of Dario Argento's work -- DEEP RED, TENEBRAE, and TRAUMA, particularly. In this regard, it's worth noting that Huston's film features a flashback to a trauma in the childhood of Susannah York's character, where she is pictured as a girl with long blonde hair and piercing eyes, in a Victorian dress, holding a ball... Could Bava have seen this film and imported the memory into his KILL, BABY... KILL!?

I found this remarkable essay about Huston's FREUD online, which comes to grips with the film biographically and psychologically far better than I could hope to do, and it also offers some fascinating behind-the-scenes information and gossip. (I didn't know, for example, that Jean-Paul Sartre had been involved in scripting it.) It's worth reading, and a film well worth tracking down. In fact, I'd compare it favorably to some of the acknowledged Huston classics, simply on the grounds that there are many other movies like them, and very few others like this. FREUD belongs on a short shelf with ALTERED STATES, THE ELEPHANT MAN, and... well, you tell me.

If anyone from Universal is listening, please let us have FREUD on DVD -- perhaps as part of a "John Huston Double Feature" with the also-missing-in-action THE LIST OF ADRIAN MESSENGER.