Thursday, December 29, 2011

Screening Diary: Wolfie and Roughie

THE PICK-UP: Sloppily-made but ambitious and attention-grabbing, this obscure 1968 roughie from R. L. (Lee) Frost first aroused fan interest when an exciting, hard-hitting trailer was included on one of Something Weird's TWISTED SEX trailer compilations. It was considered lost till one last-known surviving print was discovered, with hard Danish subtitles, in an overseas film vault. Two pick-up men are driving over a million dollars in protection money from Vegas to a mob rep in LA, but plead car trouble in order to take in a motel party with two attractive ladies picked up along the way, raising concerns at both ends of their itinerary. A bad idea turns worse when the women handcuff them and abscond with the dough, but are they in it for themselves, or are they working for someone else? The mostly handheld B&W photography is unconcerned with composition, but there are occasional arty touches like cuts to still-photo montages during the more violent moments. The dialogue is no more than you'd expect, the acting barely acceptable, but the sleazy paperback plot is pleasingly elaborate and stocked with twists and plenty of back-stabbing characters, so it plays similarly to Bava's BAY OF BLOOD; even the silly finale is not tonally unlike the surprise postscript of Bava's film. This was anonymously co-produced by David L. Friedman, who actually plays a pivotal role and seems to enjoy his long career's only bed scene with a naked lady. The library cues scoring the film are well-chosen and amount to a distinctive, edgy score. Pretty much the missing link between the 1960s roughies and the more ambitious crime sleaze epitomized by the GINGER films of the early 1970s. Viewed on Something Weird DVD-R.

Wednesday, December 28, 2011

Last Night's Screening

Tuesday, December 27, 2011

What I'm Watching

In the time I've become more casual -- indeed, lax -- about this blog, the muscle I formerly used to maintain it has grown flabby and it has begun to affect my approach to writing adversely in other ways. I think it's necessary to embrace a minor commitment like this, if only to make it that much easier to embrace more significant writing commitments. The muscle needs to be ready and prepared. So I'll not only list the films but add some comments about them as well.

I caught a bug over the holidays and am still recovering. Yesterday I didn't feel like doing much other than watching movies, so I actually watched five.

CEREMONY: The first feature written and directed by Max Winkler, the son of actor Henry Winkler, this is a moderately surprising retread of one of the perennial chick flick situations: a former boyfriend crashes the wedding of the girl he never forgot, determined to win her back. In this case, the bride is the formidable Uma Thurman, both taller and older than leading man Michael Angarano. Character is usually the saving grace of such films, and this has some memorable ones and some clever dialogue, but mostly it has the courage to go somewhere other than where the genre has taught us to expect. I liked supporting actress Brooke Bloom particularly, and was impressed by the taste of whoever selected the source music. Viewed randomly on cable.

ONE NIGHT IN THE TROPICS: Abbott & Costello's first feature casts them under their real names as amiable wise guys serving as backup to reformed gangster William Frawley. Their routines seem a bit forceably shoe-horned into a story derived from LOVE INSURANCE, one of the rare non-Charlie Chan novels written by Ohio native Earl Derr Biggers. Top-billed Allan Jones and Nancy Kelly sing, none too memorably, and THE MUMMY'S HAND's Peggy Moran has a number too, which shows singing to be not particularly her forté. Kept daydreaming throughout about how Scorsese might have worked with Costello, given the chance, because he seemed to me like a more docile Joe Pesci in this. Was surprised to discover that the "Sir Walter Raleigh" coat-over-the-puddle gag from A HARD DAY'S NIGHT was stolen from here. Viewed on Universal DVD.

BUCK PRIVATES: Abbott & Costello were the best-reviewed aspect of ONE NIGHT IN THE TROPICS, so they top-lined their second feature and first real movie vehicle. They play two sidewalk tie-selling hustlers who are chased by street cop Nat Pendelton into a movie theater that's doubling as a recruitment center, ushering them into the Army. A much better movie than their first, given additional zest by the Andrews Sisters (who melodicize their way through several numbers, including their signature tune "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy") and some impressively rubber-legged boogie-woogie dancers. Making the Army look like Heaven on earth, with free cigarettes and doughnuts and pretty WACs offering their phone numbers, this became Universal's biggest money-maker to date, which explains why some of its gags were subsequently quoted in Warner Bros. cartoons like "To Duck Or Not To Duck," which reprised some of the boxing gags. Viewed on Universal DVD.

THE SEARCH FOR BRIDEY MURPHY: I've long wanted to see this supposedly influential Paramount release, based on a best-selling real life account of a hypnotist who successfully regressed a friend's wife to a past life in Ireland. Louis Heyward hosts the film in the manner of a TV or radio show, but as the hypnotist rather than himself, walking from a bare set area onto a furnished set to answer a ringing phone that propels the plot into motion. SHADOW OF A DOUBT's Teresa Wright, deliberately muted and deprived of closeups in her early scenes, becomes the unexpected center of attention as the sessions begin. THE THING'S Kenneth Tobey plays her husband. Scripted and directed by Noel Langley (one of the screenwriters of THE WIZARD OF OZ), this is an intriguing experiment in docudrama filmmaking, and one of the earliest screen investigations into untapped areas of the mind; it's most significant success is that it manages to hold one's interest without action, relying almost entirely on Q&A dialogue derived from the original recordings. Viewed on Netflix.

LIMITLESS: I'd not heard of this one before, but I found the premise hard to resist: a blocked writer uses an experimental drug that makes the brain's entire capacity available to the user, allowing him to write a first novel in only four days before sending him off in constant search of newer, more challenging, eventually deadlier frontiers. Bradley Cooper makes a believable protagonist and Robert DeNiro lends third act gravitas as a business tycoon who elicits Cooper's aid in facilitating a corporate merger that would make him a man of unparalleled power and influence. Teeming with interesting, well-cast secondary characters and unexpected snaring incident, it's also refreshing in that it remains true to what's conceptually exhilarating about the drug, teasing the possibility of a dark outcome without finally submitting to it. Directed by Neil Burger, whose THE ILLUSIONIST I admired. Watching this, I was reminded at times of such disparate films as BRAINSTORM, STRANGE DAYS and OLDBOY. Worth seeing. Viewed on Netflix.

Friday, December 23, 2011

My Return to the NaschyCast!

Tuesday, November 01, 2011

Remembering Richard Gordon (1925-2011)

Bela Lugosi with Richard Gordon (left) and Alex Gordon (right), the origins of Monster Kid fandom.

Bela Lugosi with Richard Gordon (left) and Alex Gordon (right), the origins of Monster Kid fandom.I had to break off our conversation, engrossing and friendly and exciting as it was, because I needed to help Donna set up Video Watchdog's dealer's room table, but Dick (as he prefered to be addressed), beaming with friendly engagement, happily followed along and we continued talking as he perused issues of the magazine -- to which he promptly subscribed. I haven't done an actual head count, and don't really want to, but I strongly suspect that, in the decade-plus that followed, Dick Gordon wrote more letters to VIDEO WATCHDOG than any other reader. And, except for a couple such letters that may have fallen prey to my sometimes-less-than-professional filing system, every one was published. And proudly so.

One of the many reviewing duties presently in front of me is Tom Weaver's recent book THE HORROR HITS OF RICHARD GORDON, which now turns bittersweet. I am grateful to Tom for compiling that book in time for Dick to see it, but even moreso for being the friend to him that geography and my own disparate ambitions did not allow me to be, keeping him occupied and feeling appreciated and involved in life and film for as long as he did. I once wrote in an editorial what Dick's friendship to me, to Donna and our magazine meant to me, and I fortunately have Tom's memory, written to me, of reading that editorial to Dick and how it moved him and how he asked Tom to read it to him a second time. Thanks to Tom's sharing of that story, I felt a very real connection to Dick that transcended our first and only physical meeting twenty years ago. That's a very sweet memory and, of all the people I've known in this business over the years, it's hard to think of another memory concerning them that's as sweet in quite the same way. When he suffered a grievous personal loss a few years ago, I picked up the phone to share my condolences and we spoke as though no time had passed. I'm a bit of a mystic, and when I think of how this was possible, after nearly twenty years, and all the other criss-crossing that took place in our lives prior to our actual meeting, well, it gives one pause... to wonder, and to appreciate.

As Tom told me earlier today after relating this sad news, when I referred to Dick as the first Monster Kid, "That would be his older brother Alex, but Monster Kid Membership Card #0002 ain't too shabby." Indeed not. In observing Dick's passing, it is less his films that come to my mind and heart than this connection to the origins of Monster Kiddom I was privileged to have by sort of knowing and working with both of the Brothers Gordon. Their earlier example, so bold and enterprising, made it feel less strange and more respectable to do what I do, to love what I love, to be who I am -- and to be doing in middle age what I've been doing since I was a teenager. I am still trying to emulate them to the extent of actually breaking into the business of making films.

He passed away in hospital this afternoon at the age of 85. How serendipitous, how he would have loved knowing, that his last night on Earth would be Hallowe'en!

He'll be missed.

Friday, October 28, 2011

First Look: VIDEO WATCHDOG #165

For a fuller listing of contents and select preview pages, click "Coming Soon" on the Video Watchdog website's main page!

For a fuller listing of contents and select preview pages, click "Coming Soon" on the Video Watchdog website's main page!

Saturday, October 08, 2011

A Bad Week for Beloved Character Actors

Charles Napier (April 12, 1936 - October 5, 2011), the jut-jawed, horse-toothed, all-man actor who starred in numerous Russ Meyer pictures, was featured in several Jonathan Demme films, appeared in the classic STAR TREK episode "The Way to Eden" and, along the way, provided the roars for Lou Ferrigno's THE INCREDIBLE HULK. He was 75.

Charles Napier (April 12, 1936 - October 5, 2011), the jut-jawed, horse-toothed, all-man actor who starred in numerous Russ Meyer pictures, was featured in several Jonathan Demme films, appeared in the classic STAR TREK episode "The Way to Eden" and, along the way, provided the roars for Lou Ferrigno's THE INCREDIBLE HULK. He was 75. David Hess (September 19, 1942 - October 8, 2011), actor and musician responsible for writing Pat Boone's "Speedy Gonzales" (under the name David Dante) and for scaring the hell out of 1970s audiences with his uncomfortably real portrayals of psychopaths in Wes Craven's THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, Ruggero Deodato's THE HOUSE AT THE EDGE OF THE PARK and other thrillers. In his last film SMASH CUT (2009), he acted alongside Sasha Grey, Michael Berryman, Herschell Gordon Lewis and THE WIZARD OF GORE's Ray Sager, playing a horror film director in the recursive gore flick hommage. He and Charles Napier acted together in Deodato's BODY COUNT (1987), starring VIDEO WATCHDOG interview subject Mimsy Farmer. He was 69.

David Hess (September 19, 1942 - October 8, 2011), actor and musician responsible for writing Pat Boone's "Speedy Gonzales" (under the name David Dante) and for scaring the hell out of 1970s audiences with his uncomfortably real portrayals of psychopaths in Wes Craven's THE LAST HOUSE ON THE LEFT, Ruggero Deodato's THE HOUSE AT THE EDGE OF THE PARK and other thrillers. In his last film SMASH CUT (2009), he acted alongside Sasha Grey, Michael Berryman, Herschell Gordon Lewis and THE WIZARD OF GORE's Ray Sager, playing a horror film director in the recursive gore flick hommage. He and Charles Napier acted together in Deodato's BODY COUNT (1987), starring VIDEO WATCHDOG interview subject Mimsy Farmer. He was 69.Thursday, October 06, 2011

R.I.P. Bill Barounis of Onar Films

It has just come to my attention that Bill Barounis, the man responsible for the small but important DVD label Onar Films, passed away earlier today.

It has just come to my attention that Bill Barounis, the man responsible for the small but important DVD label Onar Films, passed away earlier today.I was not aware of it, but Bill was reportedly diagnosed with brain cancer a couple of years ago; the last update on his website mentions a stroke and being wheelchair-bound. But it is to Bill's single-minded (and often single-handed) determination and devotion to Turkish cinema that a handful of fascinating oddities, considered too outré for wider release, found their way to DVD in subtitled and extremely limited editions.

VIDEO WATCHDOG reviewed a number of Onar Films' titles in the past -- Ramsey Campbell, John Charles and David Kalat all took particular interest in the field Bill was so individually mining. I don't know if anyone else is in place to fulfill new or outstanding orders at Onar, but you might want to head over to their website, click on "Contact Us" and submit a query about the availability of their remaining titles -- or perhaps just a heartfelt message of thanks. In his own way, Bill Barounis was one of the video industry's visionaries... and obviously, he loved movies more than most.

As a reminder of his enterprising spirit, here's a link to an interview conducted with Bill a few years ago when Onar was just beginning. This photo of Bill was first published at enlejemordersertilbage.blogspot.com and we hope his friends there won't mind its use here.

Unmasking THE WAX MASK

I'm presently on a long overdue Gaston Leroux kick, acquiring and reading as many of his novels as appeared in English translation as I can find. THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA is wonderful in ways that have yet to be filmed, but there is much more to him and his contribution to the horror genre than just that. In fact, in an impressive two-part article published in the final two issues of MIDI-MINUIT FANTASTIQUE (issues 23 and 24, 1970), none other than Jean Rollin wrote in depth about horror cinema's immense debt to Leroux's literary imagination -- a debt that, among English speaking horror fans, remains largely unpaid.

I'm presently on a long overdue Gaston Leroux kick, acquiring and reading as many of his novels as appeared in English translation as I can find. THE PHANTOM OF THE OPERA is wonderful in ways that have yet to be filmed, but there is much more to him and his contribution to the horror genre than just that. In fact, in an impressive two-part article published in the final two issues of MIDI-MINUIT FANTASTIQUE (issues 23 and 24, 1970), none other than Jean Rollin wrote in depth about horror cinema's immense debt to Leroux's literary imagination -- a debt that, among English speaking horror fans, remains largely unpaid.All films about intelligent apes who learn to kill can be traced back to his novel BALAOO (even the 1932 MURDERS IN THE RUE MORGUE contains ideas that didn't originate with Poe), Roger Corman's THE HAUNTED PALACE is based on H.P. Lovecraft's "The Case of Charles Dexter Ward" but that story was itself indebted to Leroux's darkly comic THE MAN WITH THE BLACK FEATHER (also translated as THE DOUBLE LIFE), and of course every unmasking scene from THE FLY to PSYCHO to MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM owes something to PHANTOM, and so on.

Speaking of MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM, I've often wondered about the real literary basis, if any, for Sergio Stivaletti's film M.D.C. MASCHERA DI CERA (THE WAX MASK, 1997), which articles sometimes link to a Gaston Leroux novel called "THE WAX MUSEUM" or "MYSTERY OF THE WAX MUSEUM" depending on your reporter... but no such novel exists, and no screen credit was ultimately given. In the course of my collecting, I've now discovered that a short story exists, entitled "The Waxwork Museum," which was collected in translation in a 1980 story compendium called THE GASTON LEROUX BEDSIDE COMPANION, edited by Peter Haining. A foreword acknowledges that the translation by Alexander Peters first appeared in FANTASY BOOK in 1969, but no original French publication date is given. It very likely appeared in the 1910s-1920s, possibly prior to Paul Leni's classic silent picture WAXWORKS (1924).

Of related interest: in Leroux's THE MAN WITH THE BLACK FEATHER (aka THE DOUBLE LIFE OF THEOPHRASTE LONGUET), there is a chapter bearing the title "The Wax Mask"... but it has nothing to do with the story of the film.

Thursday, September 08, 2011

Someone Should Dig Up THE HORRIBLE DR. HICHCOCK

Whatever they're asking, I say it's worth it. Freda, of course, launched Italian horror with I vampiri (THE DEVIL'S COMMANDMENT, 1957, co-directed by Mario Bava), and they later collaborated again on Caltiki il mostro immortale (CALTIKI THE IMMORTAL MONSTER, 1959). HICHCOCK -- a deliberate misspelling so as not to step on Alfred's copyrighted and trademarked name and image -- stands as Freda's most defining solo outing in a genre he did not hold particularly dear. Consciously made in the image of a Roger Corman Poe picture, it is like a Poe picture adapted to grand opera, full of romantic swooning, melodramatic flourish and the icy dread of premature burial. But why the film has remained so entrenched in the popular imagination is that it deals, or appears to, with the verboten subject of necrophilia.

While watching HICHCOCK again, for the first time in a truly stellar-looking and complete presentation, I had some realizations about it and began to take notes. Rather than write something new and finished about the picture, I thought I would simply share my thoughts here.

1. The main titles encompass one of the most brilliantly inspired moments in the history of horror cinema. Halfway through the plain text-on-black main titles, they stop and the screen goes black. We think they've ended as we await the fade-in, but then the darkness is pierced by a woman's shriek! We've already been worked to a lather by Roman Vlad's appassionata nero score, so the shriek literally permits the overexcited music to release its tensions. Translation: It's an orgasm. A beat or two after the shriek ends, the main titles resume, as does Vlad's score, now sounding appropriately more subdued. I think it's horror's most brilliant main titles conceit since that fist jumped up to punch through the final glass matte credit in MGM's MAD LOVE (1935). Let's not draw any analogies to the fact that production designer Franco Fumagalli (THE GODFATHER III, THE ENGLISH PATIENT) had his name unfortunately Anglicized to "Frank Smokecocks."

2. "His Lust Was A Candle That Burned Brightest In The Shadow of the Grave!" explained the film's advertising campaign. Dr. Bernard Hichcock (Robert Flemyng) is indeed a necrophile, but as I paid close attention to the story, I realized that he doesn't really have sex with corpses. He fondles and strokes and caresses the bodies of dead women gurneyed through his ward at the University Hospital, but he always takes his stoked desires home to be properly received by his all-too-willing wife, Margaret (Maria Teresa Vianello). Bernard has developed an experimental anaesthetic, Sonneryl, to put Margaret in a more enforcedly passive state prior to their ritualized lovemaking. Unfortunately, Bernard keeps the Sonneryl in a cabinet next to an identical bottle labelled Poison.

3. Overexcited one evening by a particularly voluptuous cadaver that jiggles under the sheet as its gurney goes over a bump on the hospital floor, Bernard races home and overeagerly grabs the wrong bottle -- we think -- and injects his wife, who appears to die as a result. In fact, it later transpires that he simply overdosed her with the dark, frothing liquid (which looks like, and probably was, root beer or something comparable), resulting in a premature burial from which she was rescued by the Hichcocks' cat-stroking housekeeper and enabler, Martha (Harriet White Medin).

3. Martha's character only makes sense if we realize that she harbors lesbian desires of her own for Margaret. (Did I say "cat-stroking"?) She is obviously more devoted to Margaret than to Bernard, whom she always greets with a dutiful weariness bordering on contempt; in the first scene of his homecoming, we first see Martha signalling Margaret of his return, while wearing and projecting a knowing expression about what is impending. We sense her implicit involvement in these secret Victorian revels, but what's in it for her? Perhaps what's in it for her is availing herself of her Master's docile leftovers.

4. When Margaret "dies," Bernard returns to his home after 10 years with a new bride, Cynthia (Barbara Steele). Dialogue reveals that he met her abroad as one of his patients, who was recovering from a traumatic shock. Of course, he was doing likewise and it is inferred that his supposedly mortal error brought about a sudden end to his old habits... but. Screenwriter Ernesto Gastaldi has said that, when this film ran a week behind schedule, Freda covered himself by tearing a 12-page chunk of exposition out of the script that was never filmed. The only hole in the narrative I can find would detail Hichcock's own traumatized response to Margaret's death and his meeting with Cynthia. Gastaldi doesn't remember what failed to go before the cameras, but I'd like to think the missing exposition would show Hichcock struggling to remain immune to the charms of the corpses he saw during his retreat, and then introduce Cynthia as Bernard's patient. It wouldn't be necessary to detail their courtship; all the viewer would need is a scene of Cynthia, high-strung and overwrought, fainting in his consultation room and abandoning her young and conscious form to his covetous clutches. This would be enough to reactive Bernard's suppressed passions and make him want to legalize his possession of her.

5. One senses that Cynthia's marriage to Bernard is rooted in mutual psychological dependency rather than love or passion. Once he brings her back to his home in London and returns to the University Hospital, she soon notes to his colleague Dr. Kurt Lowe (Silvana Tranquilli, an unfortunately dull leading man) that he's become nervous and strange -- meaning the old work-related temptations are rattling him once again. Cynthia nevertheless remains safe with him, only becoming truly endangered after the point when he secures the moment of privacy at the hospital to undrape a woman's corpse and drink in the sight of its nakedness, submissiveness, and pliability.

6. There is a very creepy moment of delirium where Cynthia awakens, paralyzed and revolted, her eyelashes snarling as Raymond Durgnat once said they did, on the bier in Bernard's necrosanctum. She sees him leering near her feet, his face swelling and glowing red -- a remarkable and perhaps unique use of inflatable bladder effects in Italian makeup effects, at least at this moment in time. As bizarre as the scene is, it's greatest stroke of genius may be that it adds (unexplained) a woman's hand, clenched as if in rigor mortis, rising up behind him to drape itself companionably over his shoulder. The lack of explanation makes the moment all the more unsettling. Who is this? we wonder, and we later realize that Cynthia's subconscious was forecasting the story's truth and outcome. Steele's close-ups in this film are particularly ravishing and give the film the glorious production value of Gainsborough paintings. I'm sure she was not paid anywhere near what it was worth for her to be who she was.

7. Speaking of paintings, the clarity of the print I consulted exposed to me, for the first time, the overall shoddiness of a matte painting depicting the façade of Hichcock's villa. I imagine much of it was cropped offscreen in the earlier home video copies I'd seen. Freda himself started out as an art critic and liked to dabble in painting; it would not surprise me if this piece were his work -- it could even be a detailed colored pencil sketch, from the look of it. It's first seen as Cynthia first arrives at the villa by coach; there's a cutaway to the façade, framed by some foregrounded flora like a young tree branch, some fronds, and (literally) a potted plant -- this sort of foregrounding was an authentication trick Freda had picked up from working with Mario Bava. We later see the same matte painting during a storm (where a lightning flash causes a flat reflection of the foregrounded branch on the house's supposedly uneven surface, spoiling an already cheap illusion) and during heavy rain (with overly large hose dribbles foregrounded with the rest).

8. The climax of Dario Argento's SUSPIRIA (1977) owes everything to the climax of this film, which is another fiery inferno overseen by a hate-maddened harridan. There is a moment when Cynthia pulls back a curtain to reveal the supposedly dead Margaret standing there, looking monstrous under her veil -- a premonitory shudder of Mater Suspiriorum without a doubt. It should also be mentioned that a quality print with restored color reveals a proto-SUSPIRIA use of Technicolor in play throughout. Decades before M. Night Shayamalan's THE SIXTH SENSE (1999), cinematographer Raffaele Masciocchi inserted a red gel splash somewhere onscreen immediately prior to each horrific moment.

9. The image which the film's US distributor used for the film's poster art shows Cynthia hanging upside-down as her deranged husband poises a scalpel at her neck. The point of this image always eluded me till this viewing, but in the dialogue, Bernard clearly (albeit hurriedly) states that he intends to restore his first wife's grave-spoiled beauty with the blood of his second, younger wife. The cutting of the scene suggests that a censor, somewhere, may have demanded the removal of various shots showing Cynthia being jabbed and cut, because there is blood clearly collecting in a large white bowl placed beneath her -- a kind of proto-TEXAS CHAIN SAW MASSACRE image, if you think about it.

10. I've always known that Robert Flemyng gave his all to this unlikely project, but to see his performance in perfect clarity reveals a wealth of little nuances to cherish -- particularly in all the business he gets to do when he first goes home after a day at the hospital. We see him go to his front door, observe that his wife is entertaining at a dinner party, and gaze ruefully through a window at the gathering. This establishes his covert nature. Then he proceeds to a secreted cellar entrance, where he follows a private stairwell past his wife's company, which further establishes him as cold and antisocial. As Martha signals Margaret that he's home, that it's time to send her friends and admirers away, Bernard goes into his den, tosses back a bracing drink or two, and then clutches the key to his private necrosanctum with the jaunty, privileged air of a Victorian clubman. He is especially good when exposed to the cadavers, observing them with careful gestures and awed hushes of adoration, his fear and desire fused... and his performance reaches its fever pitch when he first realizes that Margaret may not be dead, that she may still be alive or at least available to his desires, which must be the single most operatic sequence in Italian horror.

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Notes on John Carpenter's THE WARD

THE WARD, John Carpenter's first feature in a decade (since GHOSTS OF MARS, 2001), carries his name above the title as always, but actually finds him relinquishing much of his usual control. He didn't write this film, nor did he score it, so while it does resort time and again to a familiar bag of tricks (unexpected intrusions in the foreground, periphery of the scope frame or in the depth of field), it does shows him working, admirably, outside his comfort zone and achieving his most invigorating work since 1988's THEY LIVE.

THE WARD, John Carpenter's first feature in a decade (since GHOSTS OF MARS, 2001), carries his name above the title as always, but actually finds him relinquishing much of his usual control. He didn't write this film, nor did he score it, so while it does resort time and again to a familiar bag of tricks (unexpected intrusions in the foreground, periphery of the scope frame or in the depth of field), it does shows him working, admirably, outside his comfort zone and achieving his most invigorating work since 1988's THEY LIVE.

The script by brothers Michael and Shawn Rasmussen attends the commitment of Kristen (Amber Heard) to a mental hospital following her apprehension at the scene of a house she's burned down. Installed in the experimental psych program of Dr. Stringer (MAD MEN's Jared Harris), she is surrounded there by some fairly predictable patient types (Danielle Panabaker as a beautiful scheming narcissist, Mamie Gummer as a plain hostile lesbian, Laura-Leigh as a toy-hugging child-woman, and Lyndsy Fonseca as the first to go), Kristen becomes alert to a vicious ghost (Mika Boorem) haunting her hospital ward. If the script isn't particularly ground-breaking in terms of dialogue or characterization, it keeps the viewer guessing right up to its nicely surprising explanation of events -- which, in a funny way, makes the audience feel as mentally ill as anyone onscreen -- and its traditional approach is a big part of its appeal. The story is set in 1966, when the laws governing the treatment of mental patients were more lax than they are today, making this particular story possible; in keeping with its era, cursing is kept to a minimum and the visual storytelling largely eschews CGI and staccato AVID-style editing to return to what might be called the classic principals of genre technique.

Aside from my unreserved admiration for THE THING (1982), my amusement with THEY LIVE and his sluggishly amiable Hawks pastiche ASSAULT ON PRECINCT 13 (1976), my adamant if inexplicable fascination with PRINCE OF DARKNESS (1987), and my healthy respect for the atmosphere in THE FOG (1980), I've never really bought into Carpenter as a "master of horror." He's always been more of an able technician than an auteur. That said, what horror films have become over the past decade has done a lot to alienate me from the genre, so I found THE WARD consistently entertaining because it plays like a master lesson in how to use today's technological advantages (it was shot digitally, then transfered to three-perf 35mm) hand-in-hand with those tried-and-true techniques which form the very essence of cinematic experience. One could define such techniques as those which distinguish film from television -- or, worse still, films that look and play like television, as has increasingly become the norm. This is not a film about sensation, it's about story-telling. It's not about shocking one's sensibilities, it's about surprising them. It's not about doing most of the job digitally in post, it's about being prepared on the set.

It's an interesting paradox. While I wouldn't place THE WARD above, say, HALLOWEEN (1978) as an example of Carpenter's work, HALLOWEEN has never convinced me of Carpenter's mastery of the genre, but in a strange way, THE WARD does.

THE WARD is available from Arc Entertainment on DVD and Blu-ray, as well as digital download.

Friday, August 19, 2011

"Pass The Marmalade": Jimmy Sangster (1927-2011)

Lurking in the periphery of my 1994 novel THROAT SPROCKETS is a fetching young secretary named Colleen Sangster. She was my little tribute to a special breed of snarling, enticing female anima -- personified by the likes of Valerie Gaunt, Carol Marsh, Andrée Melly and Barbara Shelley -- found in the work of a humble, workaday screenwriter whose filmic universe had become part of my own creative bedrock.

Lurking in the periphery of my 1994 novel THROAT SPROCKETS is a fetching young secretary named Colleen Sangster. She was my little tribute to a special breed of snarling, enticing female anima -- personified by the likes of Valerie Gaunt, Carol Marsh, Andrée Melly and Barbara Shelley -- found in the work of a humble, workaday screenwriter whose filmic universe had become part of my own creative bedrock.

Jimmy Sangster, who died this morning at the age of 83, tempts summation in comic book lingo: you could say he was the Stan Lee of Silver Age horror, the writer responsible for THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN (1957) and DRACULA (US: HORROR OF DRACULA, 1958), both directed by Terence Fisher for Hammer Film Productions, Ltd. -- the two films which turned the tide of horror cinema in the mid-1950s and made it a commercial genre once again after a near-decade of failing returns.

Sangster wasn't a quippy writer like Stan Lee, but he similarly revitalized a classic form of storytelling that was, at the time, becoming ossified as the motion picture medium progressed into widescreen and Technicolor. What he brought to vampire films alone is immeasurable, and he achieved what he did in part by returning to the classic texts of Mary Shelley and Bram Stoker. Under his byline, Hammer's Frankenstein films (including THE REVENGE OF FRANKENSTEIN, 1959) became the chronicle of Baron Victor Frankenstein, and his creations reflected his own blind spots, his own narcissism. Also under his byline, Hammer's Dracula films (including THE BRIDES OF DRACULA, 1960, and DRACULA - PRINCE OF DARKNESS, 1965) kept the Count himself largely offscreen, but were as imbued with his malign aura as the original novel. Most importantly, however, Sangster took us deeper into the concepts those authors gave us. In (HORROR OF) DRACULA, when Jonathan Harker discovers the mark of a vampire on his own throat, self-consciousness enters the genre: What is vampirism, when it is transfered to our protagonist and narrator?

John Van Eyssen adds an existential dimension to Jonathan Harker in HORROR OF DRACULA.

John Van Eyssen adds an existential dimension to Jonathan Harker in HORROR OF DRACULA.

We also see Professor Van Helsing graduating in DRACULA from academic knowledge of vampirism to becoming its active adversary; he is not always ahead of the game, he is sometimes taken by surprise, and in BRIDES is even victimized and left to save his own soul. His Baron Frankenstein is a brilliant autodidact and visionary, an elitist maverick, whose blue-blooded sense of privilege often proves the downfall of the higher purpose for which he spills so much common red blood.

After his first screenwriting credit (Joseph Losey's A MAN ON THE BEACH, 1955), Sangster's list of screenplay credentials form an impressive overview of Britain's contribution to fantastic cinema over four decades: X - THE UNKNOWN (1956), BLOOD OF THE VAMPIRE (1958), THE MUMMY (1959), THE MAN WHO COULD CHEAT DEATH (1959), THE HELLFIRE CLUB (1959), JACK THE RIPPER (1960), THE TERROR OF THE TONGS (1960), TASTE OF FEAR (aka SCREAM OF FEAR, 1961), THE PIRATES OF BLOOD RIVER (1961), MANIAC (1963), PARANOIAC (1963), HYSTERIA (1964), THE DEVIL-SHIP PIRATES (1964), THE NANNY (1965, his personal favorite), the Bulldog Drummond adventure DEADLIER THAN THE MALE (1967), THE ANNIVERSARY (1967), CRESCENDO (1970), Curtis Harrington's WHOEVER SLEW AUNTIE ROO? (1971), FEAR IN THE NIGHT (1971), THE LEGACY (1979) and John Huston's only foray into the genre, PHOBIA (1980). He also directed two Hammer films during their early '70s transitional period, the darkly comic HORROR OF FRANKENSTEIN (1970) and LUST FOR A VAMPIRE (1971). He also wrote several espionage novels, numerous teleplays and series scripts (including some for KOLCHAK THE NIGHT STALKER and WONDER WOMAN), and two self-effacing volumes of autobiography, the awkwardly titled DO YOU WANT IT GOOD OR TUESDAY? (1997) and INSIDE HAMMER (2001).

Joe Dante once observed that Warner Bros' advertising tag "THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN Will Haunt You Forever!" proved truer for a generation of filmgoers than their publicity department could ever have anticipated. Who could forget the Baron (Peter Cushing), supposedly bent on creating life, coldbloodedly sending his servant girl (Valerie Gaunt) to her doom at the hands of his Creature (Christopher Lee) -- because he has impregnated her? Or its glimpses of disembodied body parts -- the cinema's first in full color -- with one particularly gruesome moment dissolving to the breakfast table and the Baron's tension-shattering request "Pass the marmalade"?

Joe Dante once observed that Warner Bros' advertising tag "THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN Will Haunt You Forever!" proved truer for a generation of filmgoers than their publicity department could ever have anticipated. Who could forget the Baron (Peter Cushing), supposedly bent on creating life, coldbloodedly sending his servant girl (Valerie Gaunt) to her doom at the hands of his Creature (Christopher Lee) -- because he has impregnated her? Or its glimpses of disembodied body parts -- the cinema's first in full color -- with one particularly gruesome moment dissolving to the breakfast table and the Baron's tension-shattering request "Pass the marmalade"?

Or Jonathan Harker's (John Van Eyssen's) foolhardy mistake in (HORROR OF) DRACULA when he opts to stake the vampire bride (Valerie Gaunt) who bit him before destroying Dracula himself (Christopher Lee)? Or its classic final confrontation between Dracula and Van Helsing (which Peter Cushing improved on-set by suggesting his hero run along a tabletop and tear down a curtain to let in lethal sunlight)?

Few scenes in 1950s horror are as shocking as the high society soirée in THE REVENGE OF FRANKENSTEIN where Karl (Michael Gwynn), his misshapenness returning (and worsening to cannibalistic tendencies) after a failed cured by the Baron (Peter Cushing), crashes through the glass doors of the event AND the anonymity of the respected "Dr. Stein" in a plea for help. Likewise, few scenes of the period are as uplifting as the finale in which the Baron's associate, Dr. Hans Kleve (Francis Mathews), must use the skill he has acquired from the Baron to save his life, when his charity ward patients, learning his real identity, turn on his kindness and tear him to bits.

Andree Melly doesn't stay dead in THE BRIDES OF DRACULA.

Andree Melly doesn't stay dead in THE BRIDES OF DRACULA.

Perhaps no other vampire film mines quite so much fresh and inventive territory as THE BRIDES OF DRACULA, a Sangster script subsequently revised by two other writers, Peter Bryan and Edward Percey. In the absence of Christopher Lee, one of Dracula's disciples, Baron Meinster (David Peel) is kept imprisoned in his chateau by his doting mother (Martita Hunt), who lures young women there to feed his appetites, and perhaps to impose a kind of heterosexuality on an existence that was destroyed by socializing with men of loose morals. Here, the Baron -- once freed -- not only vampirizes his own mother, who then consents to her own destruction, but the Baron's old nanny (Freda Jackson) comes unhinged and marauds as a madly cackling midwife to the Undead, lying on the ground and helping to "birth" new vampires from their burial grounds. Here, even Van Helsing is bitten, and in an unforgettable demonstration of righteous resolve, he purifies his own neck wound with a red-hot poker and douses it with Holy water.

Sangster wrote DRACULA - PRINCE OF DARKNESS under some duress, hid behind a pseudonym ("John Sansom") to write it, and claimed he never saw it... and yet the first half of the film is enthralling, with the startling means of Dracula's resurrection and Barbara Shelley's effective transition from prim Victorian vacationer with a schedule to keep to a snarling, libido-liberated vampire bride among its many recommendations.

Ralph Bates and David Prowse in HORROR OF FRANKENSTEIN.

Sangster's films as a director were, by his own admission, less than satisfying. He loved making HORROR OF FRANKENSTEIN, calling it the happiest six weeks of his career, but he felt the result was "so lighthearted, its feet didn't touch the ground." He blamed producer interference for eroding his confidence on the set of LUST FOR A VAMPIRE, which he did not bother to supervise in its cutting or post-production. Both films, hobbled by a cheapness that no longer had Hammer's once-ingenious art director Bernard Robinson to disguise it, nevertheless have their moments and some likewise unforgettable images -- for example, Countess Carmilla Karnstein (Yutte Stensgaard), sitting erect and topless in her coffin, a victim's blood staining her bare breasts, or the young Baron (Ralph Bates) activating a severed hand with electricity so that it offers the old two-pronged salute.

"As a writer, I delivered my finished script and then went on to something new," he wrote in his autobiography. "Around six months later the picture would hit the screen. By then I'd forgotten I'd even written it."

Fortunately for the rest of us, THE CURSE OF FRANKENSTEIN will haunt us forever.

Thursday, August 18, 2011

"No, Mr. Bond - I Expect You To Die!"

The pictures accompanying the recent reports about Gérard Dépardieu peeing on the plane confirm that he is finally ripe to play Auric Goldfinger. No thanks necessary, just send me my 10 per cent.

Wednesday, August 10, 2011

Monday, June 20, 2011

Preview: SANDS OF THE KALAHARI (1965)

Coming from Olive Films (SD and Blu-ray) on August 2 is SANDS OF THE KALAHARI, a Sixties adventure film whose title is still occasionally invoked with awe by Baby Boomer matinee-goers. Now that I've finally caught up with it, I wish I'd had the pleasure of seeing it on the big screen back in the days when I had fewer movies under my belt. Not because the movie is predictable -- on the contrary, I found it quite engrossing -- but what I've learned about human nature over the years, simply by living, made some of the film's plot twists and human insights less of a surprise now than they would have been then.

Coming from Olive Films (SD and Blu-ray) on August 2 is SANDS OF THE KALAHARI, a Sixties adventure film whose title is still occasionally invoked with awe by Baby Boomer matinee-goers. Now that I've finally caught up with it, I wish I'd had the pleasure of seeing it on the big screen back in the days when I had fewer movies under my belt. Not because the movie is predictable -- on the contrary, I found it quite engrossing -- but what I've learned about human nature over the years, simply by living, made some of the film's plot twists and human insights less of a surprise now than they would have been then.Based on a novel by William Mulvihill, the set-up is familiar: a motley group of travelers inconvenienced by a cancelled flight are persuaded to charter an independent plane to their African destination rather than wait, only to have it collide with a cloud of locusts over the Kalahari desert, stranding them with only enough water to support a single man for half a day.

For its time, the images of the plane's windshield wipers and engines clotting and smearing with locust glop must have been startlingly graphic, and they're still fairly disgusting; yet it's a far more natural and cinematic reason for crashing the plane than the usual explanations such stories give. The passengers include pilot Nigel Davenport, big game hunter Stuart Whitman, doctor Theodore Bikel, German retired soldier Harry Andrews, co-producer Stanley Baker as an injured and introspective mining engineer, and Susannah York as an attractive young divorcée.

For its time, the images of the plane's windshield wipers and engines clotting and smearing with locust glop must have been startlingly graphic, and they're still fairly disgusting; yet it's a far more natural and cinematic reason for crashing the plane than the usual explanations such stories give. The passengers include pilot Nigel Davenport, big game hunter Stuart Whitman, doctor Theodore Bikel, German retired soldier Harry Andrews, co-producer Stanley Baker as an injured and introspective mining engineer, and Susannah York as an attractive young divorcée. The film was directed by Cy (Cyril) Endfield, beloved among genre fans for directing for the classic Ray Harryhausen opus, MYSTERIOUS ISLAND (1961), itself a story of survival in the wake of an air crash, and it was the sixth of his collaborations with co-producer Stanley Baker, the most famous of which was ZULU (1964). Endfield also scripted the film from Mulvihill's novel, and he does a fine job of balancing outbursts of energy with stretches of contemplation and repose, during which the story's psychological knots slowly and effectively tighten.

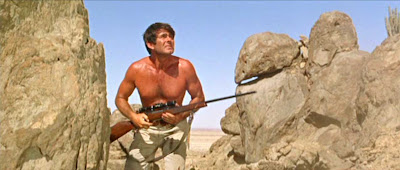

The film was directed by Cy (Cyril) Endfield, beloved among genre fans for directing for the classic Ray Harryhausen opus, MYSTERIOUS ISLAND (1961), itself a story of survival in the wake of an air crash, and it was the sixth of his collaborations with co-producer Stanley Baker, the most famous of which was ZULU (1964). Endfield also scripted the film from Mulvihill's novel, and he does a fine job of balancing outbursts of energy with stretches of contemplation and repose, during which the story's psychological knots slowly and effectively tighten. Fairly soon after the crash, Whitman strips off his shirt and grabs his rifle to become the Alpha Male of the survivors, refusing to wait for the long-toothed baboons surrounding their campsite to make the first attack. His is a remarkably physical and robust performance, very likely a career-best, and his characterization is aided by Endfield's scripting, which is careful to give the motivations for this increasingly dangerous and twisted character a sound basis in logic.

Fairly soon after the crash, Whitman strips off his shirt and grabs his rifle to become the Alpha Male of the survivors, refusing to wait for the long-toothed baboons surrounding their campsite to make the first attack. His is a remarkably physical and robust performance, very likely a career-best, and his characterization is aided by Endfield's scripting, which is careful to give the motivations for this increasingly dangerous and twisted character a sound basis in logic. Much of the film's psychological complexity orbits around the presence of York, whose perspiring blonde presence causes other animal instincts to flare among the men. (Endfield insists we think of her character in sexual terms from the beginning, practically introducing her from behind as she takes a shower.) The avuncular Bikel presumes to tacitly advise this young woman to remain sexually impartial for the sake of everyone's survival, but the men surrounding her have other ideas. Davenport's character asserts his primacy as the Captain of his passengers with an attempted rape of York. In one of the strangest twists of the film, Davenport gives up in his attempt because the tearful York submits too easily ("I'll do anything, just don't hurt me!"), which alienates him. Aware that Baker has observed him at what he tried to do, a somewhat embarrassed Davenport volunteers to cross the open desert with as much water as he can carry, in search of rescue.

Much of the film's psychological complexity orbits around the presence of York, whose perspiring blonde presence causes other animal instincts to flare among the men. (Endfield insists we think of her character in sexual terms from the beginning, practically introducing her from behind as she takes a shower.) The avuncular Bikel presumes to tacitly advise this young woman to remain sexually impartial for the sake of everyone's survival, but the men surrounding her have other ideas. Davenport's character asserts his primacy as the Captain of his passengers with an attempted rape of York. In one of the strangest twists of the film, Davenport gives up in his attempt because the tearful York submits too easily ("I'll do anything, just don't hurt me!"), which alienates him. Aware that Baker has observed him at what he tried to do, a somewhat embarrassed Davenport volunteers to cross the open desert with as much water as he can carry, in search of rescue.Interestingly, in the second attempt on York's virtue, by Whitman, he also gives up before completing his conquest because he feels that she is seducing him, which the hunter in him doesn't like. One try later, they do get together -- not out of any real affection or even liking for one another, but because she is his prey and he embodies her best chance of protection.

Stanley Baker, being mostly cave-bound and brooding into crackling fires ("This is what men used to do before television," Bikel notes), doesn't challenge either of these virile competitors for York's hand, as it were. In his own way, he loathes the same weakness in her that the other men have seen, but he sees it from another perspective and experiences it in his own unique way. As Whitman goes off the rails and begins killing the other males to preserve for himself a greater share of dwindling rations, Baker discovers the hard way that York's need to claim the fittest for her own outbids all morality and any responsibility to the others. One imagines Mulvihill's novel might offer more background about her character to help underpin the decisions she makes; in context, the lack of such background and contrast unfortunately suggest her selfish choices as archetypically female.

Stanley Baker, being mostly cave-bound and brooding into crackling fires ("This is what men used to do before television," Bikel notes), doesn't challenge either of these virile competitors for York's hand, as it were. In his own way, he loathes the same weakness in her that the other men have seen, but he sees it from another perspective and experiences it in his own unique way. As Whitman goes off the rails and begins killing the other males to preserve for himself a greater share of dwindling rations, Baker discovers the hard way that York's need to claim the fittest for her own outbids all morality and any responsibility to the others. One imagines Mulvihill's novel might offer more background about her character to help underpin the decisions she makes; in context, the lack of such background and contrast unfortunately suggest her selfish choices as archetypically female.

Handsomely photographed by Edwin Hillier (THE VALLEY OF GWANGI) in rocky desert locations settings that now aptly recall PLANET OF THE APES (1968), SANDS OF THE KALAHARI is presented here anamorphically in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The standard disc version I screened looks good on the home screen, despite some visible limitations related to age which may be somewhat bolstered by the Blu-ray. One fault that Blu-ray can't correct is that Olive Films' transfer neglects to add day-for-night tinting to a couple of broad daylight sequences clearly tagged by the dialogue for taking place at night.

Handsomely photographed by Edwin Hillier (THE VALLEY OF GWANGI) in rocky desert locations settings that now aptly recall PLANET OF THE APES (1968), SANDS OF THE KALAHARI is presented here anamorphically in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The standard disc version I screened looks good on the home screen, despite some visible limitations related to age which may be somewhat bolstered by the Blu-ray. One fault that Blu-ray can't correct is that Olive Films' transfer neglects to add day-for-night tinting to a couple of broad daylight sequences clearly tagged by the dialogue for taking place at night.

Monday, June 13, 2011

First Look: VIDEO WATCHDOG #163

Our next issue -- sporting a beautiful piece of original art by the inimitable Charlie Largent -- features Part 1 of my Eddie Constantine/Lemmy Caution retrospective (with input from his son Lemmy Constantine), an in-depth interview with Eddie's daughter and collaborator Tanya Constantine, Stephen R. Bissette's VW return with an appreciative essay about the 1967 horror feature THE FROZEN DEAD, and my DVD Spotlight on Bob Rafelson's Monkees film HEAD (which approaches it as part of a narrative arc begun with two earlier Jack Nicholson films, THE TERROR and THE TRIP).

Our next issue -- sporting a beautiful piece of original art by the inimitable Charlie Largent -- features Part 1 of my Eddie Constantine/Lemmy Caution retrospective (with input from his son Lemmy Constantine), an in-depth interview with Eddie's daughter and collaborator Tanya Constantine, Stephen R. Bissette's VW return with an appreciative essay about the 1967 horror feature THE FROZEN DEAD, and my DVD Spotlight on Bob Rafelson's Monkees film HEAD (which approaches it as part of a narrative arc begun with two earlier Jack Nicholson films, THE TERROR and THE TRIP).You can now flip through the entire issue, and read selected pages, by simply visiting our website and clicking on the Coming Soon option!

On sale July 5!

Friday, May 27, 2011

Happy 100th Birthday, Vincent Price!

This photograph was taken during our only meeting, on July 13, 1976, in Mr. Price's dressing room at Dayton, Ohio's Memorial Hall. He was rehearsing for an upcoming Kenley Players production of DAMN YANKEES, in which he played Satan. He was the first person I interviewed for MARIO BAVA ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK.

This photograph was taken during our only meeting, on July 13, 1976, in Mr. Price's dressing room at Dayton, Ohio's Memorial Hall. He was rehearsing for an upcoming Kenley Players production of DAMN YANKEES, in which he played Satan. He was the first person I interviewed for MARIO BAVA ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK.This past weekend, I had the honor of interviewing Roger Corman over two nights at the Hi-Pointe Theater in St. Louis, MO -- prior to screenings of THE TOMB OF LIGEIA and MASQUE OF THE RED DEATH -- as part of their ongoing Vincentennial celebration. My thanks to Tom Stockman and Cliff Froehlich of Cinema St. Louis for inviting me and allowing me to meet and spend quality time with my hero, under Vincent's wing, as it were.

Happy Birthday also to Sir Christopher Lee, today celebrating his 89th!

Friday, April 08, 2011

Quick Note on NIGHTMARE MOVIES

I received the new revised edition of Kim Newman's NIGHTMARE MOVIES in today's mail and have been spending a marvelous time with it. I rarely get excited about review books arriving in the mail; I hope they will excite me in due course. But this book stands out almost immediately for the quality of its writing, more particularly the quality of its insight, and as the most challenging thing for any creative mind to achieve: a masterpiece of organization. He also knows exactly what needs to be said in a short space and how each film dovetails to another by the same director or a different director working with similar themes, and delivers one knock-out punch after another. I've only pecked through it at random, but it has already shone light into some dim corners for me, showing me that I hadn't been thinking about some titles with the depth they deserved. I would be surprised if a more important book about horror movies was published this year.

I received the new revised edition of Kim Newman's NIGHTMARE MOVIES in today's mail and have been spending a marvelous time with it. I rarely get excited about review books arriving in the mail; I hope they will excite me in due course. But this book stands out almost immediately for the quality of its writing, more particularly the quality of its insight, and as the most challenging thing for any creative mind to achieve: a masterpiece of organization. He also knows exactly what needs to be said in a short space and how each film dovetails to another by the same director or a different director working with similar themes, and delivers one knock-out punch after another. I've only pecked through it at random, but it has already shone light into some dim corners for me, showing me that I hadn't been thinking about some titles with the depth they deserved. I would be surprised if a more important book about horror movies was published this year.

Friday, April 01, 2011

First Look: VIDEO WATCHDOG #162

Thursday, February 17, 2011

Gotcha, Mary Kay!

Two nights ago, I was seized by a strong desire to see Peter Bogdanovich's WHAT'S UP, DOC? (1972) again. I hadn't seen it since it played in theaters, and I remembered it as being very funny. I'm pleased to say the film holds up very well, it's still very funny, but it's most enjoyable for assembling a remarkable cast -- so many great character actors, ranging from Austin Pendleton, Kenneth Mars (who in fact died the day I watched it), Michael Murphy (whose screen energy, in a part mostly without dialogue, snaps the film to life at once), Randy Quaid, M. Emmet Walsh, an uncredited John Byner, John Hillerman (who seemed to be in everything that came out of Hollywood in the early '70s)... the list goes on and on, and the film also "introduces" Madeleine Kahn, who arguably steals the film from its stars, Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal -- both, in my opinion, uncommonly charismatic here.

Two nights ago, I was seized by a strong desire to see Peter Bogdanovich's WHAT'S UP, DOC? (1972) again. I hadn't seen it since it played in theaters, and I remembered it as being very funny. I'm pleased to say the film holds up very well, it's still very funny, but it's most enjoyable for assembling a remarkable cast -- so many great character actors, ranging from Austin Pendleton, Kenneth Mars (who in fact died the day I watched it), Michael Murphy (whose screen energy, in a part mostly without dialogue, snaps the film to life at once), Randy Quaid, M. Emmet Walsh, an uncredited John Byner, John Hillerman (who seemed to be in everything that came out of Hollywood in the early '70s)... the list goes on and on, and the film also "introduces" Madeleine Kahn, who arguably steals the film from its stars, Barbra Streisand and Ryan O'Neal -- both, in my opinion, uncommonly charismatic here.When the film reaches its courtroom finale, I noticed Liam Dunn as the hypochondriac judge and Graham Jarvis as his bailiff. Donna recognized the bailiff but couldn't place him, so I explained that Graham Jarvis had been featured in one of her favorite shows of the 1970s -- MARY HARTMAN, MARY HARTMAN -- as Charlie Haggers, doting stage husband of would-be country-western star Loretta Haggers, who was played by then-newcomer Mary Kay Place.

As soon as my mouth invoked her name, I was startled to see a young, still-undiscovered Mary Kay Place walking onscreen to deposit two of the film's plaid carrying cases on the judge's bench!

As soon as my mouth invoked her name, I was startled to see a young, still-undiscovered Mary Kay Place walking onscreen to deposit two of the film's plaid carrying cases on the judge's bench! The IMDb has no record of Mary Kay's presence in the film, as they do with John Byner's uncredited appearance, but there she is, right up front, plain as day. The IMDb lists a 1973 episode of ALL IN THE FAMILY, like MARY HARTMAN a Norman Lear production, as her first onscreen acting appearance.

The IMDb has no record of Mary Kay's presence in the film, as they do with John Byner's uncredited appearance, but there she is, right up front, plain as day. The IMDb lists a 1973 episode of ALL IN THE FAMILY, like MARY HARTMAN a Norman Lear production, as her first onscreen acting appearance. Graham Jarvis passed away in 2003, but Mary Kay Place continues to make welcome appearances in film and television, currently holding down a primary supporting role in HBO'S BIG LOVE. I've got to wonder if she and Graham had the same agent or something, or if they were even conscious of having worked together in this earlier project when they were subsequently cast as "baby boy" and wife.

Graham Jarvis passed away in 2003, but Mary Kay Place continues to make welcome appearances in film and television, currently holding down a primary supporting role in HBO'S BIG LOVE. I've got to wonder if she and Graham had the same agent or something, or if they were even conscious of having worked together in this earlier project when they were subsequently cast as "baby boy" and wife.Thursday, February 10, 2011

100 Years of Fantômas: The Early Novels

To acknowledge this important date, I decided to reprint here my essay on the original Souvestre-Allain novel, which first appeared in HORROR: ANOTHER 100 BEST BOOKS (Running Press, 2005), edited by Stephen Jones & Kim Newman. I have done this, but further browsing through my computer files unearthed a forgotten folder containing notes from my readings of the second and fourth novels of the long-running series in English translation, which I began compiling for some forgotten and unfulfilled purpose back in 2001. So I have also included these, with my apologies for overlooking the third, LE MORT QUI TUE (US: MESSENGERS OF EVIL), which was actually my favorite of those first four -- and my heartiest centenary wishes for the Lord of Terror.

FANTOMAS (February 1911)

US: FANTOMAS (1915)

FANTOMAS exploded in the heart of pre-WWI France like a bomb flung from an opera gloved hand. It was the first of 32 novels of terror written by Souvestre and Allain, all paperback originals published monthly between February 1911 and September 1913. Each volume carried the distinctive "Fantômas" logo and a chilling cover painting by Gino Starace─a severed hand clutching a roulette wheel, a nurse screaming in a room splashed with blood, a man disposing of someone's head from a hatbox─establishing their paternal ties to the American crime pulps of the 1930s and '40s. Unlike the 80-page "novels" promised on the covers of The Shadow, each new Fantômas novel was as thick as cake─actually Dickensian in its accumulation

of character and incident─and the French public reached for their pocket knives to cut its signatures with ravenous appetite.

For some reason, the Fantômas novels have been absorbed into the genre of mystery and detection, rather than into the horror genre where they truly belong. As Geoffrey O'Brien observed, "Fantômas is not a puzzle, but an intoxicant." The Starace painting on the cover of Fantômas shows the title character─"The Genius of Crime" (a phrase which Sax Rohmer would appropriate for his Dr. Fu Manchu)─in tie and tails with a black mask and glinting dagger, straddling the whole of Paris. Larger than life, he is seemingly beyond arrest, a Reign of Terror incarnate, but Inspector Juve refuses to accept this. Fantômas may seem a fantastic enlargement of earlier French literary figures such as Rocambôle and Arsène Lupin─those archetypes of "the gentleman thief"─yet the book's true villain of the piece turns out to be a very clever and tangible murderer named Gurn, whom Juve merely suspects of being Fantômas.

What elevates Fantômas to greatness, in my estimation, is that nowhere do Souvestre and Allain explicitly confirm or deny Juve's suspicions.

As the book opens, Juve summons Fantômas into being by speaking his name aloud:

"Fantômas!"

"What did you say?"

"I said: Fantômas!"

"And what does that mean?"

"Nothing... everything!"

"But what is it?"

"No one... and yet, yes, it is someone!"

"And what does this someone do?"

"Spreads terror!"

Did Fantômas exist before this moment?

Remarkably, everything that we learn about this arch-criminal originates with Juve, who holds Fantômas personally accountable for all that thwarts or vexes him. If crime lends meaning to the life of a policeman, might Fantômas be the inverse projection of a detective with a gargantuan ego? Lending credence to this interpretation is that Juve's own colleagues scoff at his belief in

this mythical Fantômas. However, as the book continues, as we repeatedly encounter characters on both sides inhabiting different disguises, Juve's paranoia slowly infects us. The more colorfully a new incidental character is described, the more heavily the stage make-up is trowelled-on, so to speak, the more we delight in sussing out whether they are in fact Fantômas, Juve, or the very person they claim to be.

Throughout the novel, one encounters characters on both sides inhabiting different guises, their ages ranging anywhere from the thirtyish Gurn to M. Etienne Rambert, who is described as twice as old. To Juve, they are all potentially Fantômas. His viewpoint slowly infects the reader, whose appetite is whetted for fantastic intrigue; the more colorfully a new incidental character is described by the authors, as they trowel on the makeup so to speak, the more the reader delights in anticipating whether they will turn out to be Juve, Fantômas, or perhaps merely the person they appear to be, as occurs with one of the book's most outlandish figures, the waggish vagrant Bouzille.

As the mystery deepens, one begins to suspect that Juve himself is Fantômas. In the course of his quixotic investigation, Juve shows himself an equal master of disguise, and when he aids and abets Charles Rambert─a young man wanted for the murder of the novel's first victim─Juve reveals himself as someone who places his personal needs and instincts above the requirements of law. Sensing a kindred spirit in this innocent fugitive, he bestows on him the new identity of "Jérôme Fandor," an alias chosen because it "sounds something like Fantômas." Thus, Juve unwittingly confesses a sense of enchantment with his foe, a dichotomy reflected elsewhere in the character of Lady Beltham, the lover and chief accomplice of Fantômas who is also the widow of a man he murdered.

In the next book JUVE CONTRE FANTOMAS, the authors persist in teasing us with the question of whether Fantômas truly exists─until the final chapter. In a perfunctory finale (at least as represented by the English translation), a figure in black is explicitly identified as Fantômas. The mystery comes to an end, but what arises in its place is one of the most seminal characters in the annals of horror fiction, comparable to Bram Stoker's Dracula in the sheer number and variety of its offspring. Notable examples include Sax Rohmer's Fu Manchu, Angela & Luciana Giussani's Diabolik, Grant Morrison's Fantomex, and that quirky Australian imitation of Clarence W. Martin, Ubique─The Scientific Bushranger.

The end of the first Fantômas cycle coincided with the onset of World War I. Pierre Souvestre─the series' prime mover─died in 1914 at the age of 40, less than one year into his military service. Marcel Allain revived the character in 1925 with a series of 34 sixteen-page magazine stories, later collected in five additional books. (A few more followed.) Though Allain's works aren't the equal of those he wrote with Souvestre, all five were translated for the English market─which can be said of only a paltry seven titles from the classic run. Of those seven, Book Three, LE MORT QUI TUE (US/UK: MESSENGERS OF EVIL, 1917), is outstanding, with Fantômas committing murders while wearing the skin of a dead man's hands for gloves, and L'AGENT SECRET (US/UK: A NEST OF SPIES, 1917), the fourth, is arguably the smoking gun behind Fritz Lang's SPIONE (US: SPIES, 1928), James Bond, and all the spy entertainment we enjoy to this day.

FANTOMAS exists in a few different English translations. The earliest, published in 1915 and credited to Jules Verne's translator Cranstoun Metcalfe, is the preferred and most complete text. The uncredited William Morrow translation (1986) is expurgated and rather too modernistic in flavor. There also exists a Mayflower Dell (UK) paperback original, published in 1966 under the bizarre title A MAD WOMAN'S PLOT. This lively, somewhat condensed translation was the work of Raymond Rudorff, who also translated Ornella Volta's novel THE VAMPIRE (1970) and whose own books include STUDIES IN FEROCITY: A BOOK OF HUMAN MONSTERS (1969) and THE DRACULA LEGEND (1972).

JUVE CONTRE FANTOMAS (March 1911)

Though the publications of the first two novels were separated by only one month, the events of THE EXPLOITS OF JUVE take place three years after the those of the first volume -- at least they do in this English translation, which did follow the first translated novel at a comparable distance.

Perhaps the most surprising episode of THE EXPLOITS OF JUVE reveals it to be a possible inspiration for one of the great future classics of mystery fiction and film. In Chapter XXIX, "Through the Window," Juve poses as a wheelchair-bound paraplegic and takes an apartment adjacent to that of Josephine, keeping an eye on her activities by using a special pair of binoculars that allow him to see what is happening at an angle opposite the direction in which he appears to be looking. One night, he spies on her and sees her reacting in horror to an unseen intruder. Looking on in horror, torn between his desire to see what will happen and not wishing to destroy his cover by racing to her aid past the concièrge downstairs, Juve waits too long and stands helpless as Josephine is flung from her window. Awakening to his greater responsibility, he races to her side, but it is too late to save her. The parallels to Cornell Woolrich's REAR WINDOW, and more particularly Alfred Hitchcock's film of it, are impossible to overlook.

Another influential touch is the rather daring conceit, for its time, of having Lady Beltham pose as the Mother Superior of the Convent at Nogent. As the novel series continued, one of the most famous Starace covers (for LE CERCUILE VIDE) depicted Juve and Fantômas, both garbed as nuns and firing pistols at one another! When Georges Franju directed a sound remake of Louis Feuillade's JUDEX in 1963, he included an hommage to JUVE CONTRE FANTOMAS by having the villainous Diana Monti (Francine Bergé) disguise herself as a nun, who is shown performing devilish acts of kidnapping and murder in her sacred habit before peeling it away from a sinful-

looking, skin-tight, danceskin prior to making an escape by water. (In the original silent Judex serial, which was Feuillade's circumspect apology for the glamorized villainy of his Fantômas chapterplays, Monti─played by Musidora─posed as a schoolteacher rather than as a nun.)

In this book, Souvestre and Allain continue to tease the reader with the question of whether or not Fantômas exists until the final chapter. It is here, in a short and somewhat perfunctory finale, that someone─a figure in a black mask and cape─is specifically addressed in the third person as Fantômas for the first time. The revelation has the distinct feel of a curiously abrupt change of plan. Just a few chapters before this, when Gurn appears before Lady Beltham in his guise as Dr. Chaleck, the villain responds coyly to her point-blank question, "Tell me, are you not, yourself─Fantômas?"

Chaleck freed himself gently, for Lady Beltham had wound her arms around his neck.

And later, after speaking of their future plans, Lady Beltham asks her beloved:

"And Fantômas? What will become of him? Of you?"

"Have I told you that I was Fantômas?" (p. 264)

Two chapters later, Lady Beltham─in her guise as the Mother Superior at the Convent at Nogent─hears a voice summon her by name:

At the sound of this voice, Lady Beltham fancied she recognized her lover.

"Nothing is madness in Fantômas!" (pp. 283-4)

The voice compels her to leave by order of Fantômas, and when she balks at this command, it reminds her, "Were you not ready to leave everything, Lady Beltham, to make a new life for yourself with... him you love?"

The careful phrasing, and the absence of a visual image, create a most ephemeral impression; it might be Gurn, but if it were Gurn, why does he not show himself? The answer might be that Gurn has recognized that Lady Beltham is not so much in love with him as in love with the possibility that he may be the larger-than-life Fantômas. He teases and lures her with the possibility into doing as he wishes, always suggesting the possibility of an alter ego, but never confessing. Considering the myriad disguises and ruses employed by Juve throughout the two novels, one may susceptibly interpret this caginess as a police trick to ensnare Lady Beltham, but as the book hastens to its cliffhanger finale, the ambiguity so key to the initial charm of the series is sacrificed.

L'AGENT SECRET ("The Secret Agent," 1911)

US: A NEST OF SPIES (1917)

A young woman known as Bobinette is conducting an affair with one Colonel Blocq, but unknown to him, is in the service of spies. On the pretext of repossessing some love letters left carelessly in a drawer, she steals an important government document in the Colonel's possession which explains the manufacture of a new military firing device. Before she is long out the door, the Colonel realizes what has happened and pursues her... but is shot dead in his taxi by a silent weapon that fires a small pin into his heart. Juve deduces that such a weapon could only be employed by one so fiendish as Fantômas, but Jérôme Fandor─who is aging into a more practical and pragmatic journalist─disagrees, arguing that the true world of wartime espionage is quite fiendish enough.

Fandor is drawn in deeper when he is approached by a young officer, Corporal Vinson, who confesses that he is a traitor to his country and intends to commit suicide, after baring his breast to the journalist. Vinson explains that he has been insidiously lured into the spy game and is in too far to withdraw. Fandor sends Vinson away for an undetermined period while, following a period of second-hand military training, he dons his uniform to see how the spy ring functions at first hand. He gets away with it for a time, but is eventually caught and imprisoned, accused of the murder of Colonel Brocq on the basis of some banknotes of the Colonel's which Fantômas cleverly arranged to have pass through his hands.

At Fandor's trial, he is acquitted on the strength of the surprise testimony of Bobinette─whom Juve has fortuitously saved from a van in which Fantômas had enclosed her with a hungry bear!─who concludes her admissions by swallowing a phial of poison. She is taken to the prison infirmary, but the novel, hastening to its final chapter after this, passes over including any definitive account of her fate. Likewise, the character of Wilhelmina─certainly the daughter of Lady Beltham (and kept in ignorance of her survival), and arguably the true daughter of Fantômas, in whose care she lives as the daughter of Baron de Naarvobeck─is abandoned on the occasion of the cotillion where she is to announce her forthcoming marriage.

The trap used by Juve to finally defeat Fantômas at Wilhelmina's cotillion involves the surprise participation of the King of Weimar, whose help Juve enlists by eminding him of the time he came to his assistance where Fantômas was concerned. This adventure, strangely enough, was not yet published but would form the next book in the series, UN ROI PRISONNIEREDE FANTOMAS (June 1911; US: A ROYAL PRISONER, 1918)─which leads one to presume that the two books were written simultaneously, and that the industrious co-authors lost track of their narrative chronology.

Due to its subject matter, A NEST OF SPIES is a more sober affair than its predecessors, with few of the flights of macabre fantasy or ingenious structural experiments that animated MESSENGERS OF EVIL, the English translation of LE MORT QUI TUE. On the other hand, it is arguably the seminal work behind the entirety of espionage entertainment, which seemingly first went global with the release of Fritz Lang's SPIONE in 1927.