Coming from Olive Films (SD and Blu-ray) on August 2 is SANDS OF THE KALAHARI, a Sixties adventure film whose title is still occasionally invoked with awe by Baby Boomer matinee-goers. Now that I've finally caught up with it, I wish I'd had the pleasure of seeing it on the big screen back in the days when I had fewer movies under my belt. Not because the movie is predictable -- on the contrary, I found it quite engrossing -- but what I've learned about human nature over the years, simply by living, made some of the film's plot twists and human insights less of a surprise now than they would have been then.

Coming from Olive Films (SD and Blu-ray) on August 2 is SANDS OF THE KALAHARI, a Sixties adventure film whose title is still occasionally invoked with awe by Baby Boomer matinee-goers. Now that I've finally caught up with it, I wish I'd had the pleasure of seeing it on the big screen back in the days when I had fewer movies under my belt. Not because the movie is predictable -- on the contrary, I found it quite engrossing -- but what I've learned about human nature over the years, simply by living, made some of the film's plot twists and human insights less of a surprise now than they would have been then.Based on a novel by William Mulvihill, the set-up is familiar: a motley group of travelers inconvenienced by a cancelled flight are persuaded to charter an independent plane to their African destination rather than wait, only to have it collide with a cloud of locusts over the Kalahari desert, stranding them with only enough water to support a single man for half a day.

For its time, the images of the plane's windshield wipers and engines clotting and smearing with locust glop must have been startlingly graphic, and they're still fairly disgusting; yet it's a far more natural and cinematic reason for crashing the plane than the usual explanations such stories give. The passengers include pilot Nigel Davenport, big game hunter Stuart Whitman, doctor Theodore Bikel, German retired soldier Harry Andrews, co-producer Stanley Baker as an injured and introspective mining engineer, and Susannah York as an attractive young divorcée.

For its time, the images of the plane's windshield wipers and engines clotting and smearing with locust glop must have been startlingly graphic, and they're still fairly disgusting; yet it's a far more natural and cinematic reason for crashing the plane than the usual explanations such stories give. The passengers include pilot Nigel Davenport, big game hunter Stuart Whitman, doctor Theodore Bikel, German retired soldier Harry Andrews, co-producer Stanley Baker as an injured and introspective mining engineer, and Susannah York as an attractive young divorcée. The film was directed by Cy (Cyril) Endfield, beloved among genre fans for directing for the classic Ray Harryhausen opus, MYSTERIOUS ISLAND (1961), itself a story of survival in the wake of an air crash, and it was the sixth of his collaborations with co-producer Stanley Baker, the most famous of which was ZULU (1964). Endfield also scripted the film from Mulvihill's novel, and he does a fine job of balancing outbursts of energy with stretches of contemplation and repose, during which the story's psychological knots slowly and effectively tighten.

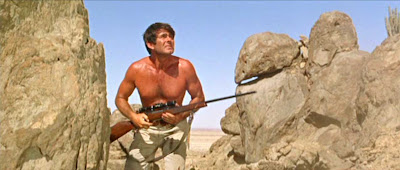

The film was directed by Cy (Cyril) Endfield, beloved among genre fans for directing for the classic Ray Harryhausen opus, MYSTERIOUS ISLAND (1961), itself a story of survival in the wake of an air crash, and it was the sixth of his collaborations with co-producer Stanley Baker, the most famous of which was ZULU (1964). Endfield also scripted the film from Mulvihill's novel, and he does a fine job of balancing outbursts of energy with stretches of contemplation and repose, during which the story's psychological knots slowly and effectively tighten. Fairly soon after the crash, Whitman strips off his shirt and grabs his rifle to become the Alpha Male of the survivors, refusing to wait for the long-toothed baboons surrounding their campsite to make the first attack. His is a remarkably physical and robust performance, very likely a career-best, and his characterization is aided by Endfield's scripting, which is careful to give the motivations for this increasingly dangerous and twisted character a sound basis in logic.

Fairly soon after the crash, Whitman strips off his shirt and grabs his rifle to become the Alpha Male of the survivors, refusing to wait for the long-toothed baboons surrounding their campsite to make the first attack. His is a remarkably physical and robust performance, very likely a career-best, and his characterization is aided by Endfield's scripting, which is careful to give the motivations for this increasingly dangerous and twisted character a sound basis in logic. Much of the film's psychological complexity orbits around the presence of York, whose perspiring blonde presence causes other animal instincts to flare among the men. (Endfield insists we think of her character in sexual terms from the beginning, practically introducing her from behind as she takes a shower.) The avuncular Bikel presumes to tacitly advise this young woman to remain sexually impartial for the sake of everyone's survival, but the men surrounding her have other ideas. Davenport's character asserts his primacy as the Captain of his passengers with an attempted rape of York. In one of the strangest twists of the film, Davenport gives up in his attempt because the tearful York submits too easily ("I'll do anything, just don't hurt me!"), which alienates him. Aware that Baker has observed him at what he tried to do, a somewhat embarrassed Davenport volunteers to cross the open desert with as much water as he can carry, in search of rescue.

Much of the film's psychological complexity orbits around the presence of York, whose perspiring blonde presence causes other animal instincts to flare among the men. (Endfield insists we think of her character in sexual terms from the beginning, practically introducing her from behind as she takes a shower.) The avuncular Bikel presumes to tacitly advise this young woman to remain sexually impartial for the sake of everyone's survival, but the men surrounding her have other ideas. Davenport's character asserts his primacy as the Captain of his passengers with an attempted rape of York. In one of the strangest twists of the film, Davenport gives up in his attempt because the tearful York submits too easily ("I'll do anything, just don't hurt me!"), which alienates him. Aware that Baker has observed him at what he tried to do, a somewhat embarrassed Davenport volunteers to cross the open desert with as much water as he can carry, in search of rescue.Interestingly, in the second attempt on York's virtue, by Whitman, he also gives up before completing his conquest because he feels that she is seducing him, which the hunter in him doesn't like. One try later, they do get together -- not out of any real affection or even liking for one another, but because she is his prey and he embodies her best chance of protection.

Stanley Baker, being mostly cave-bound and brooding into crackling fires ("This is what men used to do before television," Bikel notes), doesn't challenge either of these virile competitors for York's hand, as it were. In his own way, he loathes the same weakness in her that the other men have seen, but he sees it from another perspective and experiences it in his own unique way. As Whitman goes off the rails and begins killing the other males to preserve for himself a greater share of dwindling rations, Baker discovers the hard way that York's need to claim the fittest for her own outbids all morality and any responsibility to the others. One imagines Mulvihill's novel might offer more background about her character to help underpin the decisions she makes; in context, the lack of such background and contrast unfortunately suggest her selfish choices as archetypically female.

Stanley Baker, being mostly cave-bound and brooding into crackling fires ("This is what men used to do before television," Bikel notes), doesn't challenge either of these virile competitors for York's hand, as it were. In his own way, he loathes the same weakness in her that the other men have seen, but he sees it from another perspective and experiences it in his own unique way. As Whitman goes off the rails and begins killing the other males to preserve for himself a greater share of dwindling rations, Baker discovers the hard way that York's need to claim the fittest for her own outbids all morality and any responsibility to the others. One imagines Mulvihill's novel might offer more background about her character to help underpin the decisions she makes; in context, the lack of such background and contrast unfortunately suggest her selfish choices as archetypically female.

Handsomely photographed by Edwin Hillier (THE VALLEY OF GWANGI) in rocky desert locations settings that now aptly recall PLANET OF THE APES (1968), SANDS OF THE KALAHARI is presented here anamorphically in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The standard disc version I screened looks good on the home screen, despite some visible limitations related to age which may be somewhat bolstered by the Blu-ray. One fault that Blu-ray can't correct is that Olive Films' transfer neglects to add day-for-night tinting to a couple of broad daylight sequences clearly tagged by the dialogue for taking place at night.

Handsomely photographed by Edwin Hillier (THE VALLEY OF GWANGI) in rocky desert locations settings that now aptly recall PLANET OF THE APES (1968), SANDS OF THE KALAHARI is presented here anamorphically in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio. The standard disc version I screened looks good on the home screen, despite some visible limitations related to age which may be somewhat bolstered by the Blu-ray. One fault that Blu-ray can't correct is that Olive Films' transfer neglects to add day-for-night tinting to a couple of broad daylight sequences clearly tagged by the dialogue for taking place at night.