It's both moving and a bit alienating to read the news today that Syd Barrett has died at age 60, from diabetes-related complications. Barrett's public self died, in a sense, more than thirty years ago when he recorded his last music; or perhaps more than twenty years ago, when his last album of unreleased material was issued; or perhaps more than ten years ago, when it was all collected on a box set.

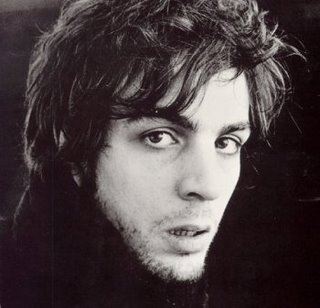

It's both moving and a bit alienating to read the news today that Syd Barrett has died at age 60, from diabetes-related complications. Barrett's public self died, in a sense, more than thirty years ago when he recorded his last music; or perhaps more than twenty years ago, when his last album of unreleased material was issued; or perhaps more than ten years ago, when it was all collected on a box set.The founding member of Pink Floyd, the author of their early singles "Arnold Layne" and "See Emily Play", the visionary responsible for taking their psychedelic noodlings into space ("Jupiter and Saturn / Oberon, Miranda and Titania / Neptune, Titan, stars can frighten..."), Barrett dropped out of the band as it finally stood on the brink of ascension above and beyond mere cult status. His closing (almost solo) song on the PIPER AT THE GATES OF DAWN album, the awkwardly pedal-toggling "Bike", showed the direction in which his songwriting craft was being lured by his acid-knurled imagination, which we're told initiated psychological problems. He withdrew from public life, abandoning music and sharing a Cambridge flat with his mother.

I have no idea who he was, or what he was like personally, but his songwriting and performing was an inspiration to later musicians like David Bowie and Robyn Hitchcock, and even to writers like me. As far as music goes, Syd Barrett was THE object lesson in the value of scrapping the traditional rules and making combinations of words and notes and tempi that suit you, because the more directly you are in touch with your own spirit, flaws and all, the more likely yours will touch others -- and, if the kiss is a bit raw, all the better. It's a lesson applicable to all the arts. I won't make the time-honored observation of the thin line dividing genius from madness, which would be lazy and presumptuous of me, but I think it's unquestionable that Barrett's three solo albums stand as some of the most original, completely unmoored, and sublimely playful and poetical music to be found in any category. His catalogue isn't dark and self-absorbed and deadly, or any of the things commonly associated with mental illness, but fractured and fanciful -- a fun place, prone to occasional wonderment and melancholy and longing, but essentially true to the emotional roller-coaster of life.

I first heard Pink Floyd after Barrett had left, with UMMAGUMMA, and I heard Syd Barrett for the first time when it was all over, basically -- when a local FM station played "Baby Lemonade" from his second solo album, BARRETT. The song's sleek but coltish feel and absurd lyrics encouraged me to seek it out, and I discovered there were far greater pleasures awaiting me on the album (which may have been the first import vinyl I ever bought): "Gigolo Aunt", the sweetly inebriated "Wined and Dined", "Maisie" (a heavy blues song sung to a cow). I'm listening to the album now, as I write this, and I find myself impressed anew by the song "Rats", which contains a wealth of inspired incantatory, impressionistic couplets, each one chanted twice ("I like the ball that brings me to / I like the cord around sinew.../ Love an empty son and guest / Dimples dangerous and blessed"). In fact, I got so deeply into BARRETT that I've never been able to take his debut solo album THE MADCAP LAUGHS into my heart on the same level, and most Barrett observers claim that it's the masterpiece and BARRETT that falls short. Perhaps the day will come when I can fully embrace THE MADCAP LAUGHS, but whenever I want to hear a nice stretch of Syd Barrett, I can't help it: I instinctively reach for BARRETT.

But when I crave the hardcore essence of this artist, it's the third album -- the odds-and-ends compilation OPEL -- that I reach for. And the opening title track is often all I really need because, somehow, this previously unreleased epic stands, for me, as Barrett's definitive musical statement. His two solo albums are sometimes described as "ragged," but they are actually very well produced and the musical ideas advanced and avant garde rather than sloppy. "Opel," however, is genuinely ragged -- no more than a demo, really -- but the album compilers had the wisdom to issue the rough-hewn song as it was, without production embellishment.

Guitar string searchings, almost tunings, arrive at the right chord, then give way to a chiming, striving rhythm as Barrett describes his own stance in a desolate yet also fantastic landscape:

On a distant shore, miles from land

Stands the ebony totem in ebony sand

A dream in a mist of gray

On a far distant shore

The pebble that stood alone

In driftwood lies half buried

Warm shallow waters sweep shells

So the cockles shine

A bare winding carcass, stark,

Shimmers as flies scoop up meat,

An empty way

Dry tears

Crisp flax squeaks tall reeds

Make a circle of gray

In a summer way (around man)

Stood on ground

At this point, the guitar makes an inspired turn toward an absolutely heartbreaking chord progression, its tonalities tragic and somehow innocently nostalgic while its cadence is almost that of a child happily skipping along. It's played only on a starkly recorded acoustic guitar, but somehow I can hear this passage (indeed the whole song) as though it were fully orchestrated and being played by orchestra, full steam ahead. As the voice returns, soaring with longing sung off-key and all the more vital for it, the chords turn bitter and brittle with an encroaching admission of yearning and struggle:

I'm trying

I'm trying to find you

To find you

I'm living

I'm giving

To find you

To find you

The entire arc of Syd Barrett's musical career is somehow encapsulated in this inspired demo. The presence of some obviously unfinished lyrics (i.e., "An empty way / Dry tears") does nothing to mar its perfection, but rather invites us more intimately into his creative process. It's this one piece of music that makes me most sad to hear that he's dead.

Whatever Syd Barrett was seeking in music, he clearly found it -- seemingly at great cost to himself. As I say, the personal Syd is a cipher to me and to most people, and I can only hope that he found more happiness in his strange, enchanted life than is commonly known. Knowing his music certainly made my life richer, and I know this is true for thousands of people. No, we can't mourn him because his death means there will be no more music, because none was forthcoming; true, his death changes nothing where most of us are concerned. But we received the messages he sent into the void in intimate places most recording artists never touch, and that's why he mattered and always will.