Last night I happened to discover Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY playing on HDNet Movies. I don't know whether or not it was the film's world high-definition premiere, but it was new to the channel and I was so impressed by what I saw, I happily strapped myself in for the remainder of the broadcast.

Last night I happened to discover Stanley Kubrick's 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY playing on HDNet Movies. I don't know whether or not it was the film's world high-definition premiere, but it was new to the channel and I was so impressed by what I saw, I happily strapped myself in for the remainder of the broadcast.I first saw 2001 the way it should be met, if at all possible -- in 70mm Super Panavision and six-track stereo sound -- circa 1975, at Cincinnati's Valley Theater, which I believe was the city's only 70mm venue at that time. The screen was immense and curved and the seats were very comfortable. I had several of my most memorable theatrical experiences there, but 2001 was supreme. In the years since, I've seen the film in many formats, from standard 35mm prints to commercial television broadcasts and the various tape and disc releases, but it was truly made for viewing in 70mm -- it loses something significant when viewed in any other format, even standard 35. That something boils down to presence.

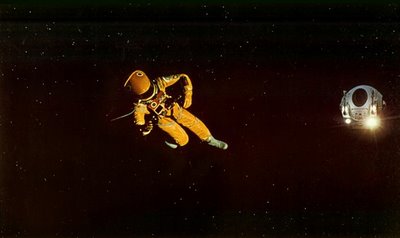

I joined the HDNet Movies presentation just as Heywood Floyd (always the accepted spelling of William Sylvester's character, or is it "Haywood Floyd," as his name is captioned on a telescreen?) was making his trip to the moon. One of the unique qualities of HD viewing is an increased awareness of composition in depth, but I've never seen that sense better explored, or exploited, than in the special effects shots from this sequence. The famous shot of the spinning parallel wheels of the space station conveyed, for the first time in my living room, an appreciable sense of its size, its dimension, and its weightlessness -- as did the later cutaway shot to the asteroids hurtling past, and the whole episode of Poole's (Gary Lockwood's) unhappy encounter with a psychotically puppeteered space pod. At its best, I find that HD also communicates a sense of temperature, and here -- in the pinpoint precision of the starry backgrounds and the razor-sharp details of the lunar surface from afar -- 2001 HD permits a sometimes frightening impression of the cold emptiness of space. Consequently, the story is heightened by being told against this subtly terrifying background of the void.

The labels on the space food trays were readable. The anti-grav toilet directions were, to some extent, readable. The detail evident in the spaceship models was astonishing. I could almost smell the fresh vinyl of the seat cushions. I noticed that misspelling of Heywood Floyd's name, and wondered, for the first time, why Bowman (Keir Dullea) left certain of HAL's memory banks connected while disconnecting him. And I was continually amazed that a film that looked this immediate, this present, could have been first released in 1968. Many of the actors in this film are now dead, but the film itself has not aged a day in nearly 40 years, and its special effects have dated least of all. It is antiquated only by a level of quality control that was unique to the eye of Stanley Kubrick, which forever closed in 1999.

In short, I found the image quality of 2001 HD to be generally as rich and as plush as it had been in 70mm, and I also found there were unexpected advantages to having the screen downsized -- in my case, to a mere 53 inches. True, one can't "inhabit" the film to the extent one can on an immense screen, but new layers of appreciation await those who can take a step back, or outside, the experience while still "feeling" it courtesy of the exquisite transfer. In my case, I found it allowed me to focus, in a way I never have before, on the calm, cool, exacting logic that guides the film from one composition to the next. Everything unfolds at an unusually pensive pace that, I realized, is perfectly analogous to a chess master inhabiting a problem, viewing it from different angles, and gradually arriving at the decision of which of these solutions is best and then advancing there. Each shot in a scene holds for as long as it takes that decision to be made, and each step forward does appear to be predicated on a logic that is there to be read in the preceding image. Granted, I've seen the film many times, but never before have I been so conscious of how many shots contain the next shot, or the idea propelling the viewer toward the next shot, or propelling the story to its next plateau.

Whether or not viewers are consciously aware of this logic, I believe they feel it and come to rely on it -- and this is why the "Jupiter and Beyond" segment remains so controversial. Because 2001 has been so unyieldingly logical and deliberate up to this point, the introduction of action and information beyond our ken is galling for many viewers. Even before I could appreciate some of the finer subtleties of this segment, I could appreciate the beauty and mystery of it -- and now that I think I have a better idea of what it's all about, my knowledge still boils down to being more receptive to that same beauty and mystery. Clearly, Bowman (Keir Dullea) undergoes an experience involving alien terrain and presence that is beyond his comprehension -- an odyssey through space and time and color that leaves him emotionally shattered. Would the film be better had Kubrick staged this segment in a manner that popcorn munchers everywhere would have easily grasped, or was he right to take us along on the same ride into the Infinite as Bowman? I think the answer is obvious, and if 2001's arrival at narrative opacity kills it as a movie for some people, that same opacity offers it endless levels available to interpretation, discussion, debate and revisitation -- the stuff of great art.

For those of you with HD service, HDNet Movies will be presenting 2001: A SPACE ODYSSEY several more times during the month, usually in showings followed by 2010: THE YEAR WE MAKE CONTACT (which, needless to say, also looks a good deal better than the transfer currently available on DVD). It's heartening to know that this exemplary transfer exists, and it proves beyond question that Stanley Kubrick was truly ahead of his time -- the HD filmmaker par excellence.