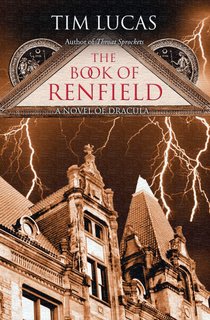

This past week -- on May 24th (Bob Dylan's 65th birthday, as a matter of fact) -- my second novel, THE BOOK OF RENFIELD: A GOSPEL OF DRACULA, quietly celebrated its first birthday, or anniversary of publication. The year has gone by very quickly. Like my first novel THROAT SPROCKETS, THE BOOK OF RENFIELD received some truly wonderful reviews (if too few overall for my liking) and didn't sell terribly well as hoped. It takes a similar approach to the Dracula legend as did Elizabeth Kostova's #1 blockbuster THE HISTORIAN, a coincidence that allowed my book to freeload on the front-of-house theme tables her book was given in various bookstore chains, but I suppose that one 700-page Dracula-related novel per year is all that most readers can handle.

When my novel came out, a week or so before HISTORIAN fever hit, I was approached by a couple of different websites with requests for interviews. Neither of them followed through, but as I was waiting, I undertook a personal exercise to become more conscious of what I had achieved with the book: I conducted a pre-interview with myself. I've long planned to complete this text and post it on the www.bookofrenfield.com website, but what with everything else that's going on, I haven't had the time. And now a whole year has gone by. But this blog needs material and I thought, given the fact of its anniversary this past week, that this partial interview might suffice. May it inform the book's earliest readers and inspire a few to hop aboard the next wave.

PS: Don't you worry. We'll get back to discussing movies one of these days.

________

THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is your second published novel, and your first in eleven years. Why did it take so long?

There's more than one answer to this. I earn my living as the publisher and editor of Video Watchdog, a monthly magazine, and these duties claim most of the hours in my day. At any one time, my wife Donna and I might be sending out one issue, working on another, and planning the next. Therefore, any time that I spend writing fiction has to be stolen from this work or other writing projects. I think anybody who's done the time will tell you there are few tasks less attractive than writing at night after you've spent all day writing. It doesn't matter that it's two different kinds of writing; that particular shifting of gears I find to be part of the problem. Also, I've spent a big chunk of the past decade finishing the manuscript of my non-fiction book, MARIO BAVA - ALL THE COLORS OF THE DARK, a critical biography of the Italian film director which I started researching back in 1975.

Despite these other demands on my time, I did write some other fiction between the two published novels. One of the projects was a novel that I'm currently back to working on, called THE ONLY CRIMINAL. I had the idea for this novel in 1977 and, over the years, it's been a short story, a novella, and more than one stillborn novel. I'm still in love with the concept, and after a very long and difficult gestation, the current draft is now singing... at least through about the first quarter of the third act. The other project was a novella called THE ART WORLD that, on the advice of a former agent, I expanded into a novel called THE COLOR OF TEARS. I'm fond of this one, in both its forms; I suppose you could call it progressive science fiction, because it's a human story that's only incidentally science fiction. It's not in print yet because my agent at the time, Lori Perkins, counseled me that it should be saved as the centerpiece of a collection of short fiction. Unfortunately, I don't seem to write short fiction. So I was actually fairly industrious during this seemingly fallow period between novels.

What made you decide to write a novel based on Bram Stoker's DRACULA?

THE BOOK OF RENFIELD was conceived for purely commercial reasons, which isn't necessarily a bad thing. A year or two after THROAT SPROCKETS was published, I was talking to Lori Perkins about what I might write next. We had both noticed that a lot ofpeople reviewing my book had compared it, sometimes favorably, to another novel called FLICKER by Theodore Roszak. Lori told me that Mr. Roszak had received a handsome advance for his new book, THE MEMOIRS OF ELIZABETH FRANKENSTEIN, and I suppose MARY REILLY was happening around this time also. Anyway, Lori suggested I think about something like that for my next book. As it happened, I had just finished reading DRACULA for the first time since high school (in Leonard Wolf's annotated edition), so the notion of a retelling of Dracula from Renfield's perspective came to me quickly. Renfield is one of the greatest and most identifiable characters in horror fiction, but he had never been the subject of his own novel before. Lori became very excited by the idea and told me to work upan outline and a fifty-page sample. This I did, writing the entire Seward foreword -- pretty much as it still reads in the novel -- in a couple of inspired sittings. The clincher was that I could deliver THE BOOK OF RENFIELD in time for it to coincide with the Dracula centenary in 1997... but, as it happened, Lori couldn't find a publisher interested in doing anything to coincide with the Dracula centenary. So the sample chapter and outline went into the proverbial drawer. For the next eight years.

Once Lori commits herself to something, she doesn't stop, and she continued to pitch the novel to anyone willing to listen. It was after discussing the book with Marcela Andres, an editor at Simon & Schuster, that Lori was advised to pitch it to another young editor at the company, Allyson E. Peltier, who had a liking for dark subjects. Ally read the sample and, after discussing it with me, decided she was interested in acquiring it... but I hadn't written a word of it in eight years... Could I deliver? Like the actor who insists he knows how to ride a horse, then does his best to learn, I said "Of course" and signed the contract... which meantthat I had to deliver it. With VW and the Bava book being written at the same time, of course.

I fought with the book a great deal, especially in its early stages, but my difficulties weren't about not knowing what to do. They were about coming to terms with certain autobiographic matters that I had chosen to share with Renfield. There were things in my past I knew that Renfield would also have to experience, but I wasn't too keen about living through those episodes again.

For example?

It's difficult to answer that question without invading the privacy of others, but I can point to the part of my dedication that specifies "my dead father and absent mother." Therein lies the personal genesis of the novel.

I was born in May 1956, six months after the death of my father. He died during reconstructive heart surgery on November 14, 1955 -- exactly one week after the birth of my wife, in the same city. Because I have never known a time when my father was not dead, this made him what you might call an "active absence" in my life; the only way I could know him was to imagine him. My mother -- widowed in her 20s, while pregnant with a son her husband didn't know was coming, went back to work (as I understand it) after I turned three, and I was subsequently placed in the homes of different families during the week. My mother would pick me up on weekends, take me to movies, buy me toys, and so forth. So, like Renfield, I was raised in strangers' homes, sleeping in rooms that weren't mine, which gave me plenty of time in which to daydream about both my absent parents, and to look forward to the weekends, when one of them would come for me.

As I describe in the novel, whenever I was placed in homes with other little boys of my own age, my introduction into the family was always seen as an invasion of their turf. Consequently, these boys would lie about me to get me into trouble, or if they were slightly older or bigger, physically beat me -- which made those times when my mother returned for me all the more important. Friday brought the joy of rescue, and Sunday night always brought the dread of going back. I didn't return to live with my own mother until the age of eight, when I was yanked out of my foster home after one of these boys (older than me by about four years) actually made an attempt on my life, succeeding in stabbing me through the foot with a butcher knife. He threatened me not to reveal my injury or risk another beating, but my limping gave it away... My mother took me to a doctor as soon as she was told, but too much time had passed for the wound to be sealed with stitches. I still have the scar, of course.

I remember reading somewhere that children do all their most important bonding with parents between the ages of three and eight, which is the exact time frame in which I was living in these cold (and sometimes dangerous) family situations as an outsider and victim. By the time I returned to live with my mother full-time, she had remarried, moved into another apartment, and was expecting another child. In fact, she and her second husband had already separated; one day, he had a yard sale without her knowledge, selling all my toys and belongings for liquor money. So when I finally got to live at home, after getting stabbed, I found that my mother wasn't the same, our home wasn't the same, and every thing I had ever owned was gone. As a child, Renfield loses everything that he owns, too -- and he voluntarily walks away from it all at another point, which I also did.

Did you have any trepidations about following THROAT SPROCKETS with another vampire-themed novel?

Of course. I don't want to be stereotyped as a vampire novelist, or even as a horror novelist. Actually, neither of my novels is much about vampirism; "oral horror" might be a more accurate description. THROAT SPROCKETS is about neck fetishism, with the puncturing of the skin by the teeth representing thebreaking of a taboo. And THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is about zoöphagy: the eating of live things.

You've never been to England, yet THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is set there, pretty much in its entirety -- and Victorian London and pre-Victorian rural England, at that. How did you make the book's geographic descriptions so believable?

I suppose the various Englands of the novel are concoctions of scenery I've retained from a lifetime of seeing movies set in suchplaces. It was easy for me to envision the dirt roads, the vicarage, the field of cat tails, the ocean crashing beyond the ledge of land. But whatever veracity the novel's geography has, is due in large part to the input of my friend and fellow novelist Kim Newman, who was kind enough to look over an early draft of the book and tell me what I'd got wrong. He was even able to tell me where Renfield's childhood took place, and the process by which Jack Seward would have travelled from Carfax to the Harkers' home for dinner. These were tremendous gifts.

What would you say to the reader who loved THROAT SPROCKETS as a progressive work of horror fiction, who might think a novel in a traditional horror mode such as THE BOOK OF RENFIELD might be a backward step for you?

The two novels have more in common than may meet the eye. Or than may meet my own eye, for that matter, since it took one of my readers -- my friend Steve Bissette, actually -- to point out to me that THE BOOK OF RENFIELD's method of bolding excerpts from the Stoker novel suggests that I am giving my readers a privileged view of pages censored from the published text of Stoker's DRACULA. It's obvious now that it's been pointed out to me, but it never consciously occurred to me asI was writing the book. Stoker's novel is public domain now, so I wasn't obliged to bold the passages which the two books share in common, but on the one hand, I felt duty-bound to give full credit to Stoker where it was due, and I also wanted my editors to know how much of my novel was written by another hand as they read it. (I should mention that the editing of the book was taken over, mid-stream, by Brett Valley after Ally Peltier resigned her post to return to school.) Hence the bolding -- it was in the manuscript, but I left it up to Brett whether to keep it or standardize the typeface for publication. It was Brett's decision to keep it, and I'm glad he did because it gives the novel a similar textual resonance to THROAT SPROCKETS that happened, as you can see, almost in spite of myself. Some readers found the fluctuating emphases of type distracting. I find it innovative, if unintentionally so; it adds another level of depth to the prose, and perhaps a unique one.

THROAT SPROCKETS was also a composite work made up of first person accounts, third person accounts, newspaper articles, television transcripts and so forth, just as THE BOOK OF RENFIELD is composed of wax cylinder recordings, diary entries, and correspondence. Because I did write THROAT SPROCKETS, I think itwould be hard, if not impossible, for me to write a book that had none of the earlier work's perspective in it, even if the story is set in a different era. Perhaps the Stoker novel interested me so, initially, because of the way it cut-and-pasted its narrative, using different fictional sources, to suggest a more plausibly realistic world. This approach dates all the way back to Daniel Defoe and his A JOURNAL OF THE PLAGUE YEAR, but there's something anticipatory of William S. Burroughs in it too, at least as I practice it.

Furthermore, I see a lot of the nameless THROAT SPROCKETS protagonist in Jack Seward, who is essentially witnessing a horrific subject, trying to piece together a whole (or at least a whole diagnosis) from the pieces of the story he is given by Renfield, and abusing himself in the process, missing out on life as it passes him by. One of the curses of being a critic as well as a novelist is that you can't help analyzing your own work, to a degree.

THE BOOK OF RENFIELD ends with a modern day chapter which surprises the reader by invoking the events of September 11. Some reviewers have criticized the novel for "going there." Any rebuttal? Any regrets?

First, let me correct you/me on two important points. First, it's the penultimate chapter; the book doesn't end there. That's an important distinction, because I felt it was essential that the novel end in the Victorian era where most of it took place. (The final chapter is one of my favorite things about the book and one of my favorite pieces of my own writing.) Secondly, the very first thing that follows the dedication page and opening epigraph is an "Editor's Note" by Martin Seward, dated 2005. This, as well as the 1939 Foreword by Dr. John L. Seward (written on the eve of World War II) should make the reader more aware and accepting, fromthe very beginning, of a time frame extended beyond the years covered by the core story.

Part of my mission in writing this book was to bring to people's attention that Stoker's novel is still wonderfully modern and still thematically relevant. A friend of mine, Richard Harland Smith, also a VIDEO WATCHDOG contributor, was a New Yorker at the time of the 9/11 attacks and he posted on the Mobius Home Video Forum a marvelous essay about reading DRACULA with his girlfriend in the wake of that nightmare and discovering how much the novel reflected the feelings and fears he was witnessing among his fellow NewYorkers by day. I reproduced that essay in my novel, in full, with Richard's kind permission. I suppose the nature of the novel tempts some people to think I made him up, and his essay too, but both are real. (You can't find it online anymore because Mobius was hacked shortly before the book came out, losing its entire history of postings. But I assure you I am not making this up.)

So that chapter isn't an instance of me being facile and unfeeling about the price America paid that day, and cyncially capitalizing on it by putting it into a vampire novel. On the contrary, it's me quoting a sincere response felt at the time by someone who was actually living in the heart of all that horror and loss and trying to make sense of it. Richard's essay actually gave my novel a point of compass, a place to go, a reason to exist. As a storyteller, I can easily see a parallel between the wrecking of the Demeter against the rocks on the coast of Whitby, which unleashed a devastating evil against a cast of sympathetic characters, and the crashing of those jets into the World Trade Center... That's what novelists do, good ones anyway: They draw parallels; they ponder life and death and God; they interpret their times. If a reader feels I'm being presumptuous by doing this, then they aren't taking the threat posed in my novel seriously enough, which is part of the point which that chapter seeks to make. Our culture has made a friend of Dracula. Some people want to read my book to share vicariously in his bloodlust, and they are disappointed.

So, to answer your/my question... No, I have no regrets about this. On the contrary, I think it's the only direction in which the novel could have gone and become something more than a literary sport based on DRACULA. And why on earth should I want to write something as unnecessary as that?

I'm still flummoxed by the PUBLISHER'S WEEKLY review that got so hung up on how well I mimicked Stoker's writing style that the reviewer found the book's overall accomplishment "dubious." THE BOOK OF RENFIELD isn't about how well I mastered the Victorian vocabulary; it's a modern story about interpreting vintage materials. It's about the importance of learning from history, and a caution against admiring and making a friend or god of evil. It also shows how the practice of evil is often tied-up with the best of intentions, like religious zeal or the hunger for love.

There's a character in this book by the name of Jolly. Why Jolly?

Because "Brown Jenkin" was taken. Seriously, I chose the name Jolly because it was the name that came to mind as the narrative took that particular turn. The name was so dead-on, it made me laugh and I was never tempted to change it. The pet mouse episode also actually happened, I regret to say, though not exactly as it occurs in the book. Mine didn't come back to life. But, then again, it didn't occur to me until years later to conduct a Moonlight Experiment...