ALIAS NICK BEAL (1949, 92:35; Kino Lorber Studio Classics): Amid Kino Lorber's monthly torrent of new releases last month was John Farrow's ALIAS NICK BEAL, a film about which - I'm ashamed to admit - I knew nothing till the other night, when I was intrigued by its trailer, included with several others on their disc of THE WEB (reviewed previously on this blog). At first glance, this Paramount picture is a sinister noir story with rote characters (heavy, tramp, bartender), a seafront locale, and lots of dense fog; its trailer presents the title character - played by Ray Milland four years after his Oscar-winning role in Billy Wilder's THE LOST WEEKEND (1945) - with heaps of mystique. He's identified as "A Man of Many Names... Many Charms... Many Victims!" but his alias is emphasized. Who IS this man, whom the hyperbole promises us we'll never forget?

Even film noir czar Eddie Muller (who does the commentary, breaking a four year "retirement") admits that he didn't get to see this film for the first time till sometime earlier in this century, and there is nothing about Kino Lorber's packaging to make potential customers more aware of what kind of film lurks behind this teasing title. Their cover makes use of the bland caricatures of Paramount's original nondescript poster art ("No Man Ever Held More Terrible Power Over A Woman!") when what it really cries out for is a more frank, more contemporary assertion of its fantastique street cred. Having seen the film and been knocked out by it, I could pout when I think of the cover an artist like Mark Maddox might have created for this release, something that would have brought its supernatural implications completely up to date.

I can't write about this film without "spoiling" the big surprise Paramount didn't want anyone to know, an astonishment that actually becomes readily apparent the first time Milland oozes onscreen: Nick Beal is the alias of Old Nick, the Devil Himself. Knowing this in advance won't spoil anything; in fact, it should only make you more conscious of layers of this film you wouldn't otherwise begin to notice till your secondary viewings - and it goes without saying that you'll want them.

Milland may be the star of the film, but he's more accurately a supporting character who puts the plot into motion and somehow stands in the background throughout by standing in our full view as a kind of slick connoisseur and enabler of human frailty. The real star of the film is third-billed Thomas Mitchell, who plays San Francisco District Attorney Joseph Foster, a baggy-faced, paunchy, happily married man of 48 (Mitchell was actually 56 but could have passed for someone ten years older) who is presented with his unspoken wish of becoming Governor and tested with moral quandaries that soon have his closest friends and even his devoted wife (the unglamorous Geraldine Wall) falling away, replaced by connected goons and a former prostitute, Donna Allen (Audrey Totter), whom Beal literally lifts out of the gutter and costumes in "sapphires, satin, and sable'" as a kind of dark knight to assail the fortress of Foster's middle-aged libido and raise his self-esteem.

Just a few years before this, Mitchell had played perhaps the most pivotal character in Frank Capra's acknowledged fantasy classic IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE (1946): Uncle Billy, whose innocent mistake at the bank causes George Bailey (James Stewart) to lose his only chance to see the world, chaining him to Bedford Falls as its last wall of defense against it becoming Pottersville. In some ways, ALIAS NICK BEAL is very much the flip side of IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE; instead of George being shown the proof of his importance by an angel, Foster is tempted by another fallen angel - THE fallen angel - with the achievement of all his personal desires as a feature-length test of character.

As fine as Mitchell is in this role, it's really the people around him that give the picture its life. George Macready, whose facial scar and raspy voice cast him as many a villain, gets a rare opportunity here to play an earnest man of the cloth and steals the film's most decisive moment with an action maneuver that would have done Peter Cushing's Van Helsing proud. Geraldine Wall has the difficult assignment of portraying a neglected wife whose love for her husband keeps her strong and civil and ever-supportive, and Audrey Totter is magnificent, the impressive focus of almost every scene she inhabits. (She reminds me a lot of Jennifer Blaire, who showed a real knack for acting in the mode of this era in Larry Blamire's mystery spoof DARK AND STORMY NIGHT.) Of particular note is a scene she plays twice - first with Milland, then with Mitchell - as Nick coaches Donna in what to say during her imminent meeting with Foster in order to keep him on the hook, with Nick somehow knowing Foster's lines in the as-yet-to-occur scene as well as the ones he's feeding to her. An impressively meta moment for its time, the scene deconstructs the acting and directing process while keeping the story in forward motion and, and when the time comes for the rehearsal to be played for real, with Nick spying on them (and seeming to conduct their actions) with one upraised eyebrow from the bedroom door, Totter manages to convey Donna's true conflicted emotions as she mouths the phony dialogue.

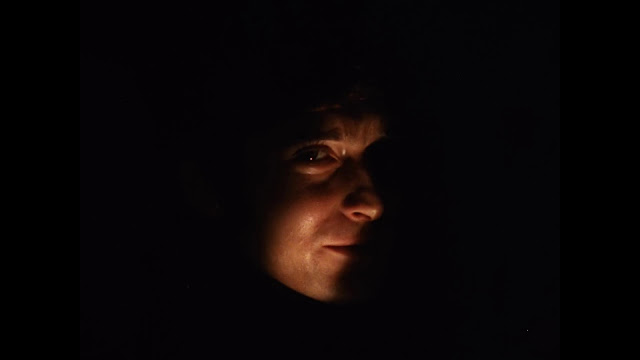

Milland approaches the role of Nick Beal with real élan - each and every one of his appearances comes as a startlement and, in a brilliant piece of script construction, his plan is first put into action by a young emissary who similarly appears and vanishes without a trace. His poise, his Mephistophelean pride, his slinky bearing, his austere refusal to be touched are brilliant brushstrokes and - now that I've seen and appreciated his work here - I can appreciate on an entirely new level why he was a good choice to play the leads in Roger Corman's PREMATURE BURIAL (1963) and X - THE MAN WITH THE X-RAY EYES (1963). The supporting cast includes a number of welcome faces, ranging from Fred Clark and Nestor Paiva to Philip Van Zandt (unbilled, happy to deliver a single line) and Percy Helton (ditto - maybe the straightest line reading he ever had).

Much of this film's brilliance is due to screenwriter Jonathan Latimer, a mystery novelist who wrote a few of the books upon which Universal's CRIME CLUB programmers were based, and later went on to become one of PERRY MASON's top TV scribes. The previous year, Latimer had worked with director John Farrow and Ray Milland on the noir classic THE BIG CLOCK (1948) - but this is their real masterpiece. The atmospheric cinematography is the work of Lionel Lindon, whose achievements include CONQUEST OF SPACE, AROUND THE WORLD IN 80 DAYS, THE BLACK SCORPION and numerous classic episodes of THRILLER ("Well of Doom," "Pigeons From Hell"), ALFRED HITCHCOCK PRESENTS and THE ALFRED HITCHCOCK HOUR, and NIGHT GALLERY (the entire second season). The score by Franz Waxman is doled out only in brief bursts but is impressive nonetheless, and in a way that complements most particularly the audacious décor given to the apartment Nick provides to Donna, where the fireplace and bed are heralded by panoramic Dalíesque murals.

Anyone with a love of fantastic cinema should feel an obligation to know this film, and know it well. This is a picture to be shelved alongside Mitchell Leisen's DEATH TAKES A HOLIDAY (1934), William Dieterle's THE DEVIL AND DANIEL WEBSTER (ALL THAT MONEY CAN BUY, 1941), Maurice Tourneur's CARNIVAL OF SINNERS (La main du diable, 1943), and IT'S A WONDERFUL LIFE.

Subscribe to Tim Lucas / Video WatchBlog by Email

If you enjoy Video WatchBlog, your kind support will help to ensure its continued frequency and broader reach of coverage.